Chesterton and the Jews

FAQ

Brandon Vogt and Nancy Carpentier Brown

“Indeed, I was a warm admirer of Gilbert Chesterton. Apart from his delightful art and his genius in many directions, he was, as you know, a great religionist . . . I deeply respected him. When Hitlerism came, he was one of the first to speak out with all the directness and frankness of a great and unabashed spirit. Blessing to his memory!”

— Rabbi Stephen Wise

President of the American Jewish Congress (1937)

These words were offered one year after G.K. Chesterton’s death by Rabbi Stephen Wise, the most important American Jewish leader in the 1930’s and 40’s, who served as President of both the American Jewish Congress and the World Jewish Congress.

In light of this praise from a prominent rabbi, you may find it surprising that there have been people over the years who have accused Chesterton of being antisemitic.

G.K. Chesterton was not antisemitic. He was not racist. He detested racism and was an ardent opponent of racial theories, including antisemitism. He fought for human dignity and affirmed the brotherhood of all men.

Why, then, has he been accused of antisemitism? Why do some people suggest he despised the Jews?

G.K. Chesterton wrote over a hundred books, thousands of articles, and nine million words in his lifetime—a staggering output. Yet a small number of critics have taken a small number of quotes from Chesterton’s massive corpus out of context, offering them as “proof” that he hated the Jews.

However, this is untrue. The quotes in question, when understood in context, don’t really mean what critics claim. We assert with confidence what virtually all readers of Chesterton intuit: racism is utterly incompatible with the mind and heart of G.K. Chesterton.

Although Chesterton was not perfect, he was neither racist nor antisemitic.

To [Chesterton] all men were brothers, not because he held it as an opinion, but because he felt it as a fact in his own case. That was for him the sole and all-sufficient basis of democracy, which he held to have for its one foundation the dogma of the divine origin of man.

— E.C. Bentley, “The Spectator,” June 19, 1936

This FAQ page is meant to clarify the issue. The Quick Questions lay out basic facts, while the rest of the FAQ goes into more detail for those wanting a deeper understanding.

Table of Contents

Quick Questions

- Who was G.K. Chesterton?

- Was G.K. Chesterton antisemitic? Did he hate the Jews?

- Why do some people claim he was antisemitic?

- Does the Society of G.K. Chesterton condone antisemitism?

- Has the Society of G.K. Chesterton ever “downplayed,” “covered-up,” or “suppressed” the accusation of Chesterton’s antisemitism?

- Why are you defending him from such a heinous charge?

Chesterton and the Jews

- What was Chesterton’s basic attitude toward the Jews?

- Did Chesterton have any close Jewish friends?

- Why was Chesterton so harsh toward Jewish financiers and bankers?

- What is Zionism and why did Chesterton support it?

- Did Chesterton rely on stereotypes for his Jewish characters?

- Did Chesterton suggest that Jews should be required to wear special clothing?

Chesterton on Hitler and the Nazis

- Did Chesterton defend Hitler? Did he really say, “I do not believe that Hitler is altogether a bad fellow”?

- Did Chesterton say, “Hitlerism is almost entirely of Jewish origin”?

- What did Chesterton say about Nazis?

- Did Chesterton really say rich Jews should be sent to concentration camps? And have Chesterton fans covered that up?

Other Criticisms

- What about the nasty, antisemitic open letter Chesterton wrote to Rufus Isaacs (Lord Reading)?

- Where can I learn more about the Marconi Scandal?

- What about Simon Mayers’ book, Chesterton’s Jews?

- What about Dawn Eden Goldstein’s talk on Chesterton and the Jews at the recent Chesterton Conference?

- What about Richard Ingrams’ book, The Sins of G.K. Chesterton?

How to Read Chesterton (Properly)

What Now?

Quick Questions

Who was G.K. Chesterton?

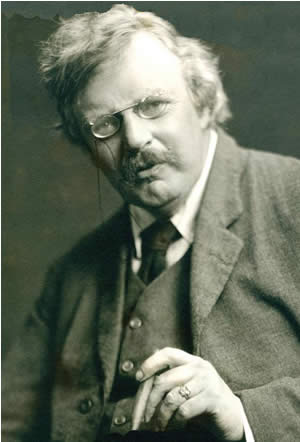

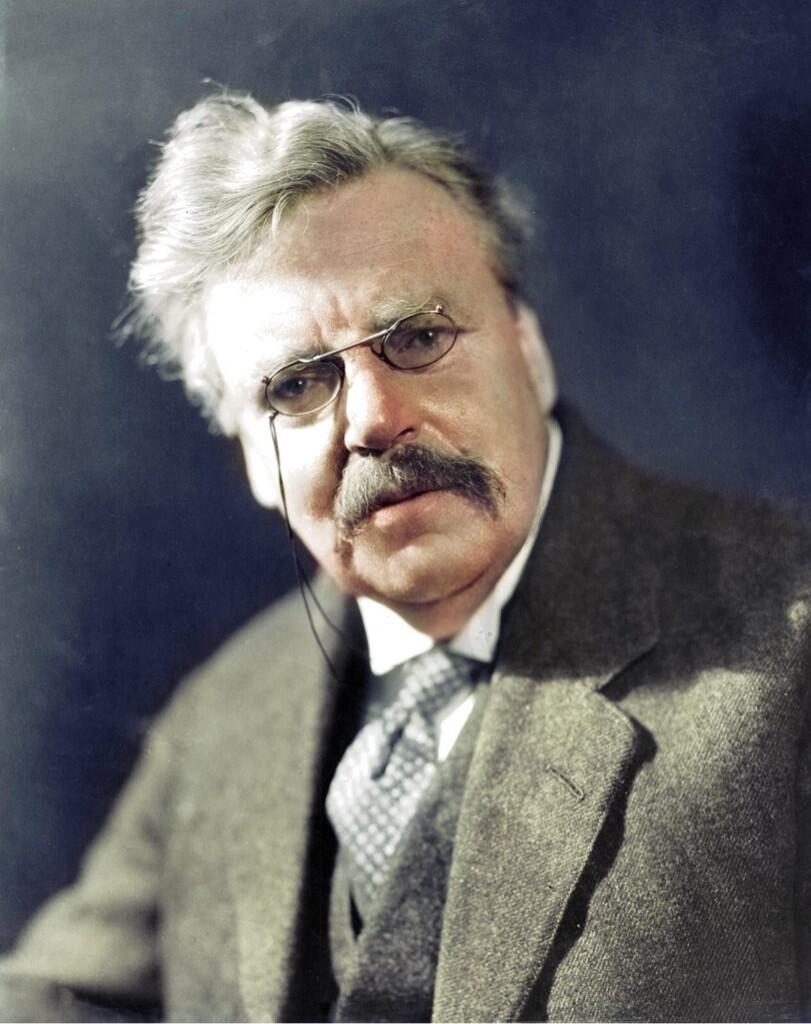

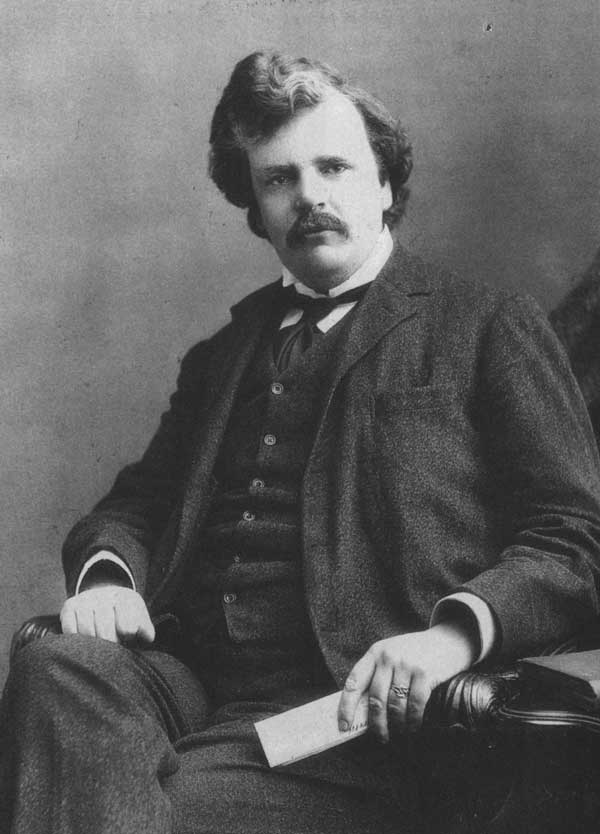

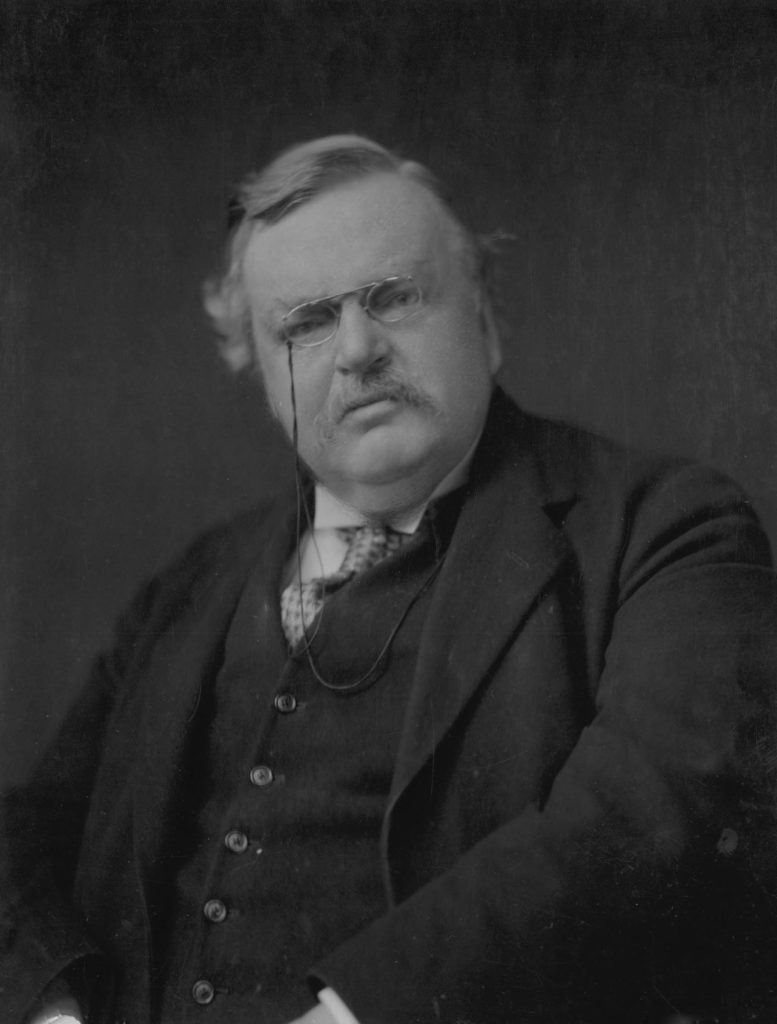

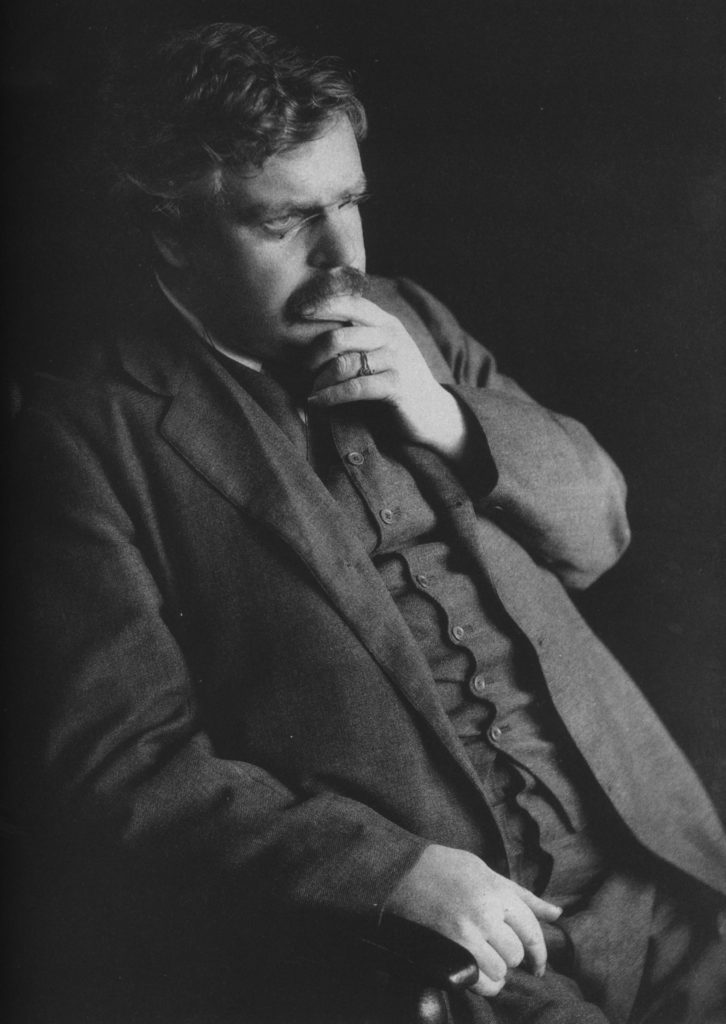

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874-1936) was a prolific English writer who achieved fame as an essayist, poet, novelist, journalist, and author of a popular detective series featuring the priest-sleuth, Father Brown. He wrote over a hundred books that have sold millions of copies.

In 1922, he shocked the literary establishment by converting to Catholicism, thereby becoming the most famous Catholic convert of the twentieth century. He was later eulogized by Pope Pius XI as “a gifted defender of the faith,” and there is presently a popular movement to have him canonized.

Though his literary status went into eclipse after his death, he has lately enjoyed a wide revival of interest as dozens of his books have come back into print and active Chesterton Societies have formed all around the world to read and discuss his work.

Even more recently, a rapidly growing network of 50 classical Catholic high schools has developed, each school named for Chesterton because he exemplified the Catholic faith through a life filled with joy, wonder, gratitude, and common sense

Was G.K. Chesterton antisemitic? Did he hate the Jews?

No. Chesterton was a friend and defender of the Jews. He flatly stated, “I am no antisemite. I respect and have the deepest regard for Jews, for their wonderful history, for their wonderful faith, and for their remarkably fine qualities, mental and moral.”

He also claimed, “The world owes God to the Jews,” and in 1933, when interviewed by the Jewish Chronicle, he said he “will die defending the last Jew in Europe.” (Chesterton said this six years before Pope Pius XI issued his encyclical condemning the German Reich.)

Chesterton had lifelong Jewish friends (see below), and prominent Jewish leaders and rabbis sought him out, celebrating his support for Zionism, both during his lifetime and after his death.

Chesterton’s writings have converted antisemites, including Joseph Pearce and Stuart McCullough (see below), leading them to abandon their racial prejudices.

G.K Chesterton was not antisemitic. That charge is false, baseless, and insulting to a man who loved, befriended, and defended the Jews.

Why do some people claim he was antisemitic?

Among the millions of words Chesterton wrote, a few passages about the Jews can be twisted to sound antisemitic when pulled out of context and interpreted in the worst possible way.

Chesterton did at times speak critically about broad groups of people, such as bankers, politicians, scientists, literary reviewers, educators, the Irish, the Prussians, the English (his own people, whom he criticized most harshly), and, yes, also the Jews. He jabbed and joked with a broad brush and engaged in stereotyping, actions today we could consider inconsiderate. But such jabs were not rooted in malice or racism. At worst, they were insensitive, especially by today’s standards.

Yet critics claim the real and more serious issue is Chesterton’s lament about “the Jewish Problem.” When read out of context, and in a post-Holocaust age, this sounds like something Hitler might have complained about. After all, Hitler offered his Final Solution to his perceived Jewish problem.

However, when writing about “the Jewish Problem”—better called “the Jewish question”—Chesterton wasn’t implying that the Jews were a problem, as Hitler believed, but that they had a problem, namely that they were a nation without a country. They lacked a homeland. And Chesterton wanted to help them solve that problem, which is why, with support from Jewish friends, he became an ardent Zionist.

Chesterton was convinced that without a homeland, the Jewish people lacked a native place to protect and develop, a place to serve as a refuge from attack. He predicted Jews would thus become vulnerable nomads who were never truly at home in any country, always seen as suspicious outsiders, thus putting them at risk for violent persecution—which is exactly what happened in the 1940s, after Chesterton’s death. In truth, Chesterton’s concerns were meant to help the Jewish people, not denigrate them. Like a prophet, he raised the alarm as their friend and defender, not as their enemy.

The confusion in this case is typical. Critics of Chesterton often pluck a line or phrase out of context, claiming it exposes deep antisemitism, when it actually affirms the opposite.

These critics are treated with more specificity and detail below. But suffice it to say, Chesterton was not antisemitic and he did not despise the Jews.

Does the Society of G.K. Chesterton condone antisemitism?

Absolutely not. We stand with the Catholic Church in condemning antisemitism in all its forms. We agree with Pope Pius XI who said, “It is not possible for Christians to take part in antisemitism.” We echo the Second Vatican Council in decrying “hatred, persecutions, displays of antisemitism, directed against Jews at any time and by anyone.” We love our Jewish brothers and sisters.

If Chesterton ever wrote anything that was actually antisemitic, we would be the first to denounce it.

Has the Society of G.K. Chesterton ever “downplayed,” “covered-up,” or “suppressed” the accusation of Chesterton’s antisemitism?

No. Chesterton was accused of being antisemitic during his own lifetime, a charge he vigorously denied, so it is nothing new or surprising. However, those who have extensively read and studied Chesterton have always believed his own testimony, that he was not antisemitic.

Rather than ignoring the charge, over the last several decades the Society of G.K. Chesterton has published numerous articles and even whole issues of our magazine on this charge of antisemitism.

We have also devoted time and energy to making all of Chesterton’s writings easily and freely available online, through the Chesterton Digital Library, so that any person can see for themselves what Chesterton actually said in context. Rather than downplaying or hiding Chesterton’s writings, we have aimed to make them more broadly available.

The accusation that we have “downplayed” or “covered up” Chesterton’s racism is ludicrous. It stems from the fact that we simply cannot agree that Chesterton was antisemitic.

Why are you defending him from such a heinous charge?

Because we are convinced the charge is false. Critics have suggested that Chesterton should not be defended against such a horrible accusation. That is certainly one way to end a debate. But we would meekly suggest that merely asserting something doesn’t make it true; accusing someone of a crime doesn’t certify their guilt.

We think wrongfully accused people should not be abandoned, but should be defended with all the vigor we can muster. That’s not because we uncritically idolize Chesterton, or support disgraceful behavior such as antisemitism—we find it repellent—but because we support the truth and stand with the innocent.

Chesterton and the Jews

What was Chesterton’s basic attitude toward the Jews?

Chesterton praised the Jews as a “noble and historic” people. He described them as creative, artistic, brilliant, resourceful, disciplined, and devoted to their families. (Note that while Chesterton sometimes criticized groups too broadly, he also praised them broadly. He described the Jews as noble, creative, and brilliant despite individual exceptions.)

Chesterton said the whole world is in their debt, for in ancient times it was the Jews who were faithful to God amidst the gods. And near the end of his life, when he saw a growing threat to the Jews in Europe, he said he would die defending the Jewish people.

Did Chesterton have any close Jewish friends?

Yes. Chesterton had lifelong Jewish friends who cherished their friendship with him. Some of these friends were wary at first because they had (wrongly) been told that Chesterton was antisemitic, but once they befriended him they learned that was a lie fabricated by opponents.

We list some of these friendships below not because they exonerate Chesterton from the charge of antisemitism; of course, someone saying “I have Jewish friends” doesn’t preclude them from being antisemitic. But the closeness and devotion of Chesterton’s Jewish friends should at least give serious pause to those who claim he despised the Jews.

- Maurice Solomon — Maurice was one of Chesterton’s original Junior Debate Club friends from boyhood. Chesterton had to plead with Edmund Clerihew Bentley to let Maurice into their circle of friends, as Bentley was reluctant to let a Jew join their group. Bentley not only overcame his prejudice, thanks to Chesterton, but ended up presenting the first book of clerihews (a type of poem invented by Bentley and Chesterton) to Maurice. For Chesterton’s nineteenth birthday, Maurice gave Chesterton a book of stories and poems by Bret Harte, signed “To Gilbert Chesterton, from his sincere friend, Maurice Solomon.” Later in life, Maurice moved to Beaconsfield, Chesterton’s town, specifically to live closer to Chesterton.

- Lawrence Solomon — Lawrence, the brother of Maurice, would also become one of Chesterton’s closest friends. He was a Professor of History at the University of London, but when Chesterton moved to Beaconsfield, Lawrence left London and bought a home in Beaconsfield so that he, like Maurice, could live close to Chesterton.

- Waldo d’Avigdor — Chesterton dedicated The Innocence of Father Brown to Waldo and his wife, Mildred (formerly Wain, a childhood friend of Chesterton’s.) Chesterton and Waldo shared a lifelong friendship.

- Digby d’Avigdor — Digby, the brother of Waldo, attended grade school with Chesterton. Digby’s school friends could not understand why he would associate with Chesterton, whereas Digby thought it an honor to be his friend: “There is no half-way house about it, I used to wonder why [Chesterton] was decent to me.”

All four Jewish friends attended G.K. Chesterton’s funeral and lamented the loss of their dear friend.

Why was Chesterton so harsh toward Jewish financiers and bankers?

Chesterton was very critical of anyone who preyed on the poor, and this especially included moneylenders, for whom he reserved his harshest criticism. Chesterton referred to these financiers, many of whom were Jewish, as “usurers.” Usury involves charging exorbitant interest or fees on the loaning of money, a practice explicitly condemned in the Bible. (Think of modern payday loan or cash advance centers, which are strategically placed in poorer neighborhoods.)

Chesterton believed usury was deeply wrong as it exploited the most vulnerable among us, the poor and marginalized. Plus it was a manifestation of greed. This was behind his harsh criticism of Jewish moneylenders. It was not because he had a low view of Jews, but a high view. He denounced their predatory behavior because he felt Scripture-believing people such as Jews and Christians should especially know better than to take advantage of the poor.

(Chesterton wasn’t alone in this criticism. Even Jewish leaders, such as Dr. Max Nordau, whom Chesterton called “the most brilliant Jew of this age,” criticized Jewish millionaires, saying, “These money-pots who despise what we honour and honour what we despise . . . Many of them forsake Judaism and we wish them God-speed, only regretting that they are at all of Jewish blood, though but of the dregs.”)

What is Zionism and why did Chesterton support it?

Zionism is a movement for the re-establishment of a Jewish nation in what is now Israel, allowing Jewish people a country, a home, in which to live and flourish. Chesterton believed every people should have a home. He used the same reasoning to support Indians ruling and controlling India, rather than the English, which prompted Gandhi to fight for an independent India (Ghandi specifically cited Chesterton as a major influence in his activism.) Chesterton believed every kind of people, like the English, should have a country to love and defend.

Similar to the biblical prophets, Chesterton prodded his religious brothers and sisters to see that “to be a nation without a country” diminishes God’s plan for his people. Chesterton stands with the great David Ben-Gurion, the principal national founder of the State of Israel, and the land of Israel today is proof that Chesterton was right. At a time when Zionism was an unpopular position, Chesterton believed if Jews were able to reestablish a homeland, the privileges of nationhood would come with that establishment: freedom, security, common culture, and common traditions. Jewish Zionists welcomed Chesterton as an important ally and warmly hosted him on a trip to Palestine in 1920.

Some critics of Chesterton have argued that Chesterton supported Zionism to rid England of its Jews, but this is untrue. His desire was for his Jewish brothers and sisters to have their own land and country—if they also wanted that. And Chesterton never insisted that Palestine was the only place for a Jewish homeland, but certainly the most logical and historical place. Most Jews agreed with him. The idea was never banishment, but autonomy and nationhood for the Jews.

However, while Chesterton supported Zionism, he did have concerns about its implementation. In the last chapter of his book The New Jerusalem, titled “The Problem of Zionism,” Chesterton says:

“I have tried to state fairly the case for Zionism, for the reason already stated . . . but I do not disguise the enormous difficulties of doing it in the particular conditions of Palestine. In fact the greatest of the real difficulties of Zionism is that it has to take place in Zion.”

(It’s worth noting that Hitler hated Zionism. In fact, in his manifesto Mein Kampf, Hitler claimed that Zionism is what led to his antisemitism, so strongly did he oppose the idea of a Jewish homeland in Palestine or anywhere else.)

Did Chesterton rely on stereotypes for his Jewish characters?

Chesterton’s novels are all larger-than-life fantastic tales. Every character is exaggerated, whether Scottish, British, Muslim, atheist, Catholic, Jew, or gentile. Exaggerating characteristics while writing fiction is not only common, but almost a necessity in order to distinguish characters from each other. (For example, see the works of Shakespeare, who was a principal exemplar of this technique. His depiction of Shylock in The Merchant of Venice relies on several Jewish stereotypes.)

Chesterton’s Jewish characters are exaggerations, just as are all his fictional characters. But this is no sign of racism or antisemitism. Again, at best it involved stereotyping that would be considered insensitive by today’s standards.

That said, it’s important to note that there are more Gentile villains in Chesterton’s fiction than Jewish ones. Moreover, a number of Chesterton’s seemingly villainous Jewish characters are only villainous at first blush; in the end, several turn out to be vindicated in his stories (e.g., “The Actor and the Alibi”). When one takes into account the wider panoply of Chesterton’s literary creations, one sees, that there is no consistent “good Gentile/bad Jew” dichotomy.

Did Chesterton suggest that Jews should be required to wear special clothing?

Yes. Chesterton believed the Jews should wear distinctive clothing. But he also believed the English should wear distinctive clothing, along with the French, Germans, Poles, and people from all nations. Chesterton believed each nation should celebrate its culture to the full by cultivating national pride through national dress, as well as through crafts, dance, and food. Chesterton always considered the Jewish people a nation, and wished for them to have the same kind of national pride as other nations. This is why he supported Zionism for those Jews who also wanted to have a restored homeland, and it’s why he thought they should proudly wear national dress.

Once again, what we have here is not antisemitism, but in fact a celebration of the Jewish people. Chesterton wanted Jews to wear special clothing because he thought they were special, just as he wanted to celebrate the English, French, Germans, and Poles with special clothing of their own.

Of course, we moderns living after the Holocaust might cringe at any suggestion of Jews wearing special clothing, as it recalls memories of Nazis forcing Jews to wear yellow badges with the Star of David, and eventually striped prison outfits. But Chesterton died in 1936, long before this clothing was introduced, and long before the Holocaust.

For more on Chesterton’s feelings about national dress, see his novel The Napoleon of Notting Hill, in which King Oberon writes a Magna Carta of Suburbs which declares all London areas to be independent cities, each with their own coats of arms, mottos, heraldic colors, and squads of city guards dressed in national colors. Chesterton also discusses this idea in his book, The New Jerusalem, in a chapter called “The Problem of Zionism.”

Chesterton on Hitler and the Nazis

“Public figures from Winston Churchill to [H.G.] Wells proposed remedies for the ‘Jewish problem’—the seemingly endless cycle of anti-Jewish persecution—all shaped by their worldviews. As patriots, Churchill and Chesterton embraced Zionism; both were among the first to defend the Jews from Nazism.”

— Ann Farmer, author of Chesterton and the Jews: Friend, Critic, Defender

Did Chesterton defend Hitler? Did he really say, “I do not believe that Hitler is altogether a bad fellow”?

In a 1934 essay titled “The Tool”, Chesterton said:

I may possibly cause some surprise, if I conclude the composite portrait by saying that in certain aspects, and under certain limitations, I do not believe that Hitler is altogether a bad fellow; and that he is almost certainly a much better fellow than the men who are going to use him.

Note that this essay was written in 1934, shortly after Hitler became chancellor of Germany, yet long before the Holocaust, Nazi murders, concentration camps, and gas chambers.

Chesterton knew very little about Hitler at the time. Per usual, he sought to see the best in other people—even his opponents. In this essay, he observed how, at least early in Hitler’s reign, Hitler called to the German mind “the virtues of peasants and the vices of usurers,” and that Hitler was reported to have been “a brave soldier in the field, and doubtless lived the hard life of soldiering with firmness, patience, and obedience.” Again, Chesterton squinted to see the best in him.

Here we’d like to quote from the beginning of the essay, “The Tool”, which was the third in a three part series about Hitler:

I am devoting three articles, of which this is the third, to a few aspects of Adolf Hitler, who has risen to such baffling and bewildering importance, or at least prominence, in the present problem of Christendom.

The first article, which I called “The Crank”, was intended to suggest that he is not exactly a normal German, any more than a normal Austrian; but is a certain modern type produced by the shallow modern education combined with the drifting modern homelessness; the man who has a smattering of subjects in general, especially of one subject; some half-baked cultural crudity like the Swastika or the Aryan race.

In the second, which I called “The Gangster”, I suggested that we must add to this something that may well make a type so naturally obscure turn into a type almost unnaturally arresting and arrogant; the vanity of the criminal; the bloodshot egoism that can actually brag of brutality.

Chesterton believed Hitler to be a “crank,” a “gangster,” and a “tool” being used by others. Like others at the time, Chesterton was under the impression that Hitler was a simple-minded puppet, propped up by more powerful and sinister Germans who were actually pulling his strings.

This explains why, in a 1936 essay titled “Why Did He Do It?”, Chesterton was notably soft in his description of Hitler.

Hitler may be cranky but not crazy. He is not literally a lunatic . . . I have always said that there were healthy elements in Hitlerism, and even in Hitler; indeed I rather suspect that Hitler is one of the healthy elements in Hitlerism. I fancy he is a better man than the men around him or behind him; such as the roaring atheist who conducted his educational propaganda or a low Prussian bully like [Hermann] Göring, who shouted down a witness in a court of justice with the schoolboy threat of what he would do to him if he got him outside.

Chesterton’s point was not to defend Hitler, but to suggest that Hitler wasn’t the biggest problem in Germany. Of course, we now know in retrospect that this assumption was disastrously wrong. Hitler was the biggest problem in Germany, and, indeed, in the world. He was monstrously evil.

But Chesterton didn’t know how evil Hitler was—he couldn’t have known. Chesterton died in June 1936, long before Hitler’s evil was fully exposed. And the limited information Chesterton received about Hitler before 1936 had been filtered by the propaganda machines in both Germany and England. Chesterton was sadly ignorant of who Hitler really was. Therefore, we should read his attempts to find some scrap of goodness in Hitler not as a defense of the ruthless dictator or as support for his evil acts, but as a sign of charity.

It’s also worth noting that Chesterton did come to see the dangers of Hitler and his regime, warning the world long before many others had taken note of der Führer. Chesterton warned especially against Hitler’s racial theories, which were rooted in German philosophers such as Nietzsche, about whom Chesterton had also warned the world.

In April 1933, Chesterton referred to “the madness of Mr. Hitler.” Then in September 1933, six years before the start of World War II, Chesterton said in an interview with the Jewish Chronicle:

I am appalled by the Hitlerite atrocities. They have absolutely no reason or logic behind them. It is quite obviously the expedient of a man who has been driven to seeking a scapegoat, and has found with relief the most famous scapegoat in European history, the Jewish people.

Shortly after that, Chesterton was asked, “What in your opinion was the stupidest thing of 1933?” He replied:

I can answer it very simply if I may be permitted to answer it sincerely. By far the stupidest thing done, not only in the last year, but in the last two or three centuries, was the acceptance by the Germans of the Dictatorship of Hitler.

In his Christmas message of 1935, he said:

We live in a terrible time, of war and rumour of war. . . to make vivid the horrors of destruction and mere disciplined murder we must see them more simply as attacks on the hearth and the human family; and feel about Hitler as men felt about Herod.

A search of Chesterton’s writings between 1933 and 1936, the last three years of his life, finds him speaking out against Hitler and Hitlerism over 150 times.

These are Chesterton’s actual opinions of Adolf Hitler. Chesterton did not ultimately defend Hitler or his atrocities, and we can be sure that had Chesterton lived another five years and seen the evils of the Holocaust, his outrage against Hitler would have only intensified.

Did Chesterton say, “Hitlerism is almost entirely of Jewish origin”?

Chesterton began a 1933 essay titled “The Judaism of Hitler” by saying:

Hitlerism is almost entirely of Jewish origin. . . [O]n top of that idea of Race, came the grand, imperial, and insane idea of a Chosen Race, of a sacred seed that is, as the Kaiser said, the salt of the earth; of a people that is God’s favourite and guided by him, in a sense in which he does not guide other and lesser peoples. And if anybody asks where anybody got that idea, there is only one possible or conceivable answer. He got it from the Jews.

To properly understand Chesterton’s point here, two things must be kept in mind. First, Chesterton wrote this essay in 1933, long before what we today know fully as “Hitlerism.” Hitler had just been appointed chancellor of Germany a few months prior, in January 1933. So, every time Chesterton referred to “Hitlerism” in the essay, he had in mind only those few months—not the Holocaust, not concentration camps, not gas chambers, not Hitler’s Final Solution against the Jews. By “Hitlerism,” Chesterton primarily meant Hitler’s ideology that the Aryans were God’s Chosen Race.

Second, this is a perfect example of sentences pulled out of context. It takes reading the entire essay to understand Chesterton’s point (that’s why we have linked the essay, so you can read the whole thing.) Chesterton was trying to explain how the Germans appropriated ideas from other cultures, such as imperialism from the Romans and militarism from the French. Ironically, Chesterton observed, they got their key idea of a Chosen Race not from Hitler but from the Jews, the object of Hitler’s scorn. Chesterton wrote:

People like the Hitlerites never had any ideas of their own; they got this idea indirectly through the Protestants, that is primarily through the Prussians; but they got it originally from the Jews.

Chesterton observed how this idea of a Chosen People had devolved over the centuries so that, for some, being the Chosen People had become an excuse for racial superiority, which the Hitlerites appropriated, “seeing their religion as a mystical religion of Race.”

He gave an example in another essay from 1934 titled “A Queer Choice”:

I have just read a passage in a pamphlet of the extreme German-Christian school, which states positively about the Germans, ‘God Himself has pronounced us His chosen people.’ . . . Here we have the Hitlerites themselves, in plain words, saying they are a Chosen Race. . . [T]he truly tribal German does imagine that he inherits some such heroic quality with the colour of his hair.

Chesterton believed this was wrong, that it was racist, and that we all should fight against the dangerous idea of racial superiority. He appealed especially to his fellow Christians, saying in the essay’s final line, “[U]ntil we have utterly destroyed it [racial superiority] among Christians, we shall never restore Christendom.” Until racism was purged from Christian Germany, all of Christendom would suffer.

This was not victim blaming. Chesterton was not faulting the Jews for Hitler’s atrocious crimes. He was merely observing the irony that the key idea fueling the Germans’ persecution of the Jews, that the Aryans were God’s Chosen Race, was an idea pirated from the very people they aimed to persecute. In the end, his essay wasn’t intended to be a slight against the Jews, but against the Germans.

What did Chesterton say about Nazis?

As early as 1911, Chesterton warned that an outbreak of violence would erupt in Europe, specifically aimed at the Jews. In an interview with The Jewish Chronicle, Chesterton said that for “Jews who are anxious to see the Jewish question solved,” Zionism seemed the right course, otherwise “history will go on repeating itself for the Jew,” referring to the historical pattern of persecution.

When Hitler began his rise to power, Chesterton warned that the Nazi leader was making Jews his scapegoat, and when the first news of the concentration camps began to emerge, Chesterton condemned Hitler and Germany, in no uncertain terms, while other writers remained silent. He predicted that there would be a new war, that it would start on the Polish border, and it would be the worst war in human history. He died before those prophecies were fulfilled.

Did Chesterton really say rich Jews should be sent to concentration camps? And have Chesterton fans covered that up?

In 2013, the blogger and online Chesterton critic Simon Mayers noted that in a 1935 essay entitled “On War Books”, Chesterton condemned “Herr Hitler and his group” for “beat[ing] and bully[ing] poor Jews in concentration camps.” But then Chesterton added, “What is even worse, they [the Nazis] do not beat or bully rich Jews who are at the head of big banking houses.”

Chesterton wrote this essay in 1935, and then five years later it was published in a posthumous essay collection titled The End of the Armistice, edited by Frank Sheed. However, the book version of the essay omitted the sentence lamenting that rich banking Jews had escaped beating and bullying. Presumably the decision to remove the sentence was made by Sheed, the book’s editor and publisher.

In a talk at the 2021 Chesterton Conference, Dawn Eden Goldstein, who learned of this sentence from Simon Mayers’ blog post, claimed that Sheed removed the sentence for the 1940 book because the sentence was so blatantly antisemitic. She further claimed that once Sheed removed the sentence, another “crime,” the crime of cover up, was committed by Ignatius Press, which published The End of the Armistice and its edited version of the essay in its Collected Works of G.K. Chesterton. Goldstein accused Ignatius Press and the entire Society of G.K. Chesterton of suppressing the offending sentence to protect Chesterton’s virtuous reputation.

Now, before drawing any conclusions about these claims, we need to answer three questions. First, what did Chesterton mean when he wrote that sentence? Second, why did Sheed remove it? Third, have Ignatius Press and the Society of G.K. Chesterton tried to suppress the sentence?

First, what did Chesterton mean when he wrote this sentence? Within the context of the article, and taking into consideration Chesterton’s usual sarcasm and wit, the sentence is not about antisemitism at all. Chesterton wasn’t celebrating Jews being dragged into concentration camps, which he deplored repeatedly throughout the 1930s. He was condemning the fact that Jewish bankers were conspiring with Nazis and getting rich from the Nazi regime, even as their fellow Jews were being persecuted by those same Nazis. Chesterton was condemning the hypocrisy of the Nazis and the betrayal of Jewish bankers.

Now, if you’re unfamiliar with Chesterton’s satirical style, and if you strip this one line out of context and interpret it in the worst possible way, you might arrive at the faulty conclusion that Mayers and Goldstein did, that Chesterton here is suggesting rich Jewish bankers be sent to concentration camps. But that clearly wasn’t his point. His point was that Jewish bankers should not conspire with Nazis, getting rich by betraying their own people. In truth, the sentence is not antisemitic in any way—just the opposite. Chesterton is condemning the Nazis and those who conspire with them to persecute poor Jews.

But then the second question: why did Frank Sheed decide to remove this sentence? Unless we find definitive evidence, the honest answer is, “We don’t know.” We can only guess at Sheed’s motives. Of course, Goldstein shows no such humility and simply assumes, without evidence, that Sheed deemed the sentence “too antisemitic” and therefore removed it in order to protect Chesterton’s reputation and “suppress” his antisemitism.

However, Frank Sheed was an experienced editor and publisher. He knew, as all good editors know, that sometimes passages are removed not because they are bad in themselves, but because they might be confusing and open to misinterpretation. Sometimes it’s better to drop a potentially distracting line, especially if it doesn’t contribute much to the overarching point of the essay or book.

That seems to be the case here. It’s likely Sheed was aware that some readers, a small minority, might have missed Chesterton’s sarcastic point and misinterpreted the line as promoting antisemitism, and Sheed thought it better to just remove the line to avoid that confusion—not because the line was antisemitic, but because some people might mistakenly read it that way. Again, this is what good editors do, and Sheed was a good editor.

Which brings us to the third question: have Ignatius Press and the Society of G.K. Chesterton actively covered up this sentence, or tried to hide its omission? This is a serious charge made by Goldstein because it involves not simply the failure to acknowledge an omitted sentence but its active suppression. (Again, Goldstein provided no evidence for her claim. She merely asserted it.)

Have these organizations performed a cover up? The answer is certainly no. Ignatius Press published the massive Collected Works of G.K. Chesterton series, which included the book The End of the Armistice. And the book included Frank Sheed’s edited version of the essay. So, Ignatius Press reprinted The End of the Armistice just as the book was originally printed.

Unless there is evidence to the contrary, it doesn’t seem Ignatius Press was aware that in this book, Frank Sheed had dropped a line from the original version of the essay. But how could they have known? To become aware of that change, they would have had to spend countless hours comparing every word in Frank Sheed’s book to every essay in the original G.K.’s Weekly columns, a task too large for almost any publisher, let alone any individual person. And besides, they had no reason to suspect there were any substantial differences between the two versions. So, there was no cover up involved, as Goldstein claimed. Likewise, the Society of G.K. Chesterton has not suppressed or covered up this line. That’s simply false.

Finally, in her talk at the Chesterton Conference, Goldstein noted that the renowned Catholic philosopher Dietrich von Hildebrand gave his wife, Alice, permission to burn Hildebrand’s unfavorable writings after his death, to safeguard any imprudent or offensive lines. Goldstein suggested the same should have been done to Chesterton’s egregious writings after his death. However, it’s tough to see how an editor (Frank Sheed) removing a line after Chesterton’s death is substantially different than his wife burning a line after his death, or how the Chesterton Society might be praised for doing the right thing (burning) in one case, but accused of hiding the information in the other. It seems Goldstein is both asking Chesterton supporters to hide (burn) Chesterton’s writings and vilifying those who possibly did so.

In conclusion, with the sentence in question, Chesterton was decrying the fact that rich Jews were in collusion with Nazi Germany. He was not suggesting that rich Jews should literally be sent to concentration camps. His point was that the rich Jews were treated differently by the Nazis. The Nazis were hypocrites for beating Jewish people but only if they were poor, not rich, and only if they were of no use to the Nazis. Chesterton was exposing yet another layer of evil in the Hitler/Nazi regime.

Other Criticisms

Below we discuss other specific criticisms raised by those who believe Chesterton was antisemitic. We will not discuss every possible case, but we’ve selected the most regularly cited examples, hoping to show that Chesterton, when read properly in context, is not guilty of what his critics accuse.

What about the nasty, antisemitic open letter Chesterton wrote to Rufus Isaacs (Lord Reading)?

In 1918, less than a week after his brother Cecil died during World War I, G.K. Chesterton published an open letter to Rufus Isaacs (aka Lord Reading). Chesterton was not in his best form. He was grieving and angry, under duress, and the letter lacked his usual charity towards all men.

In his autobiography, Chesterton himself admitted the letter was an “odd reaction.” In the letter, he described Reading, who had just been appointed British Ambassador to the United States and elevated to the House of Lords, as “a man who is a standing joke against England.” He added, “You are in practice a blot on the English landscape.” Those barbs sound just as sharp today as they did in 1918, without context or explanation. The letter’s final line, a quote from the Bible, states, “Go in Peace; but go.” Those who wish to think the worst of Gilbert suggest he was asking Isaacs to leave the country, or perhaps go to hell, but Chesterton never specified where he was asking Isaacs to go. Perhaps Chesterton just meant, “Go away; leave me alone.”

Critics such as Richard Ingrams describe the letter as “hateful.” The letter is certainly harsh and critical, and the point could be made that it should never have been published. Unfortunately, there was no one in Chesterton’s circle to dissuade him, some friend who could have stopped him, a fellow writer, or even his wife. Gilbert himself was editor of the paper in which it was published, and he allowed it to run against his own better judgment.

But what to make of the letter? To understand it, we should know that Chesterton and Isaacs had a bitter personal history. Isaacs was involved in what became known as the Marconi Scandal. This scandal was covered extensively by The New Witness, a newspaper edited by Chesterton’s brother, Cecil, a paper devoted to exposing government corruption.

Here’s the Marconi Scandal in a nutshell: in 1912, the Marconi Wireless Company was about to be awarded a huge government contract, and the business manager, Godfrey Isaacs—Rufus’s brother—not only purchased several thousand shares of stock, but sold some to cabinet members at a discounted price, including his brother, Rufus (then the Attorney General) and David Lloyd George (future Prime Minister of the United Kingdom).

In short, these English leaders received low-priced stock in the Marconi company, stock which would explode in value after the government contract became public. They would each profit enormously.

It happened that the most prominent Marconi players were Jewish. Of course, Cecil exposed the corruption because of their behavior, not because of their nationality. Nevertheless, it soon turned into a racially-charged scandal.

After the news broke, a Parliamentary inquiry took place. Rufus gave deceptive testimony, and coupled with being a member of the majority party, he was given a minimal reprimand. The other culprits escaped serious punishment as well. To make matters worse, Godfrey Isaacs then turned around and sued The New Witness for libel, hiring the leading lawyers in England—who were also members of Parliament and had felt the sting of Cecil’s pen. The trial was not about the truth of Cecil’s statements, whether the Isaacs were guilty of corruption, but whether those statements had done damage to Godfrey’s reputation. G.K. Chesterton sat in court every day, and testified on Cecil’s behalf. Yet Cecil, defending himself without a lawyer during the preliminary hearings, was found guilty of libel.

As a result of this whole saga, Rufus had tried to resign his government post but was refused. Instead, he rose in government, and in 1913, was made Lord Chief Justice. Cecil enlisted as a soldier in World War I, and tragically died in a military hospital at the end of the war.

The whole episode left Chesterton understandably bitter, and it hung in the background of this letter to Rufus Isaacs. Chesterton saw his brother humiliated and treated unjustly before sacrificing his life for his country, while the perpetrators of the crime not only went unpunished but thrived. Chesterton knew Rufus participated in insider trading and got away with it, eventually rising to the highest ranks of government, while Cecil, the writer who helped expose the crime, was punished for libel and died during the war. After Cecil’s death, Chesterton’s frustration boiled over into this open letter.

Again, the letter was certainly uncharitable. At one point, taking a shot at Rufus’ brother Godfrey, Chesterton says, “You are far more unhappy [than me]; for your brother is still alive.” However, there is nothing antisemitic within the letter. It has been used as evidence of Chesterton’s antisemitism, but only because it was a mean letter written to a man who was Jewish.

The letter has never been suppressed or covered up. You can read the entire letter here. It has been published in numerous books, including the very first biography written about Chesterton, by Maisie Ward, titled Gilbert Keith Chesterton. Also, Ian Ker’s magisterial biography, G.K. Chesterton: A Biography, goes almost line by line through the letter, explaining Chesterton’s references and meaning.

Where can I learn more about the Marconi Scandal?

The best place to start is chapter 19 of Maisie Ward’s biography, Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1943), which walks through the Marconi trial in great detail.

From there, read Lord Reading: The Life of Rufus Isaacs, First Marquess of Reading by H. Montgomery Hyde (1967) and The Marconi Scandal by Frances Donaldson (1962).

Also consider the account of Cecil’s wife, Ada Chesterton, in her book titled The Chestertons (1941). Interestingly, Ada admits that she, not Cecil, was the power behind the libelous attack on Godfrey Isaacs.

In truth, G.K. Chesterton probably misjudged Rufus Isaacs, not because Isaacs was Jewish, but because of Chesterton’s presumption that Isaacs knew it was wrong to buy the Marconi stock. Some defenders argue that while Isaacs may have acted imprudently, not considering the scandal of his actions, Isaacs didn’t do anything technically wrong. At the time, there were no English laws prohibiting this sort of insider trading, however unethical it might be.

One outcome of the Marconi affair was that it gave the Prime Minister [H.H. Asquith] the opportunity to formulate a set of rules to govern ministerial conduct in the future.

He divided them into rules of obligation and rules of prudence. One of the former was that “Ministers should scrupulously avoid speculative investments in securities as to which, from their position and their special means of early or confidential information, they have or may have an advantage over other people in anticipating market changes.” The most pertinent rule of prudence was that “in these matters such persons should carefully avoid all transactions which can give colour or countenance to the belief that they are doing anything which the rules of obligation forbid.”

It was this rule of prudence, said Asquith, which “in my opinion and in the opinion of my right honourable friends and colleagues was not fully observed [in the Marconi incident], though with complete innocence of intention, in this case.”- H. Montgomery Hyde, in “Lord Reading: The Life of Rufus Isaacs, First Marquess of Reading,” 160-161

However, it cannot be that Rufus acted with “complete innocence,” as he initially hesitated before purchasing the Marconi shares because, as he said, “he thought it better that he should have no dealings with his brother Godfrey in view of the latter’s position . . . and that company’s relations with the British Government” [ibid, 126]

What about Simon Mayers’ book, Chesterton’s Jews?

Those who accuse Chesterton of antisemitism often rely on the writings of Simon Mayers, an independent scholar and blogger who self-published a short book on Amazon in 2013 titled Chesterton’s Jews: Stereotypes and Caricatures in the Literature and Journalism of G.K. Chesterton.

The book is full of inaccuracies and bias, and was generally dismissed by scholars. In fact, only one scholarly review has ever been written about it. That review, published in the Journal for the Study of Antisemitism, said:

Chesterton's Jews reads as an activist response. . . As a work of scholarship, however, while offering promise in its central argument, the volume suffers from its activist tone and lack of development in the areas of historical contextualization, nuanced distinctions, and questions asked.

Nevertheless, most of the claims offered by Mayers in his book are addressed in this FAQ.

What about Dawn Eden Goldstein’s talk on Chesterton and the Jews at the recent Chesterton Conference?

On July 30, 2021, Dawn Eden Goldstein gave a talk at the 40th Annual Chesterton Conference titled, “Chesterton and My Jewish/Catholic Journey.”

Goldstein converted from Judaism to Catholicism in part through Chesterton’s influence. However, in her talk, based mostly on the writings of Simon Mayers, she accused Chesterton of antisemitism and the Society of G.K. Chesterton of failing to reckon with this serious failing. We have prepared a detailed, line-by-line response to Goldstein’s talk here.

What about Richard Ingrams’ book, The Sins of G.K. Chesterton?

In 2021, Richard Ingrams authored a book that, once again, accused Chesterton of antisemitism. Unfortunately, Ingrams’ claims are neither new nor convincing. Rather than focusing on Chesterton himself, most of the book impugns Chesterton’s brother (Cecil), sister-in-law (Ada), and close friend (Hilaire Belloc) for racist views, and then tries to condemn Chesterton for his association with them. Brandon Vogt and Nancy Carpentier Brown have reviewed Ingrams’ book and responded to his accusations here.

How to Read Chesterton (Properly)

For the fair-minded reader interested in examining Chesterton’s views on the Jews, we offer these principles to keep in mind.

Disliking Someone is Not Racist

G.K. Chesterton liked most people. He had an enormous capacity for friendship. Still, there were people he disliked. For example, there was a fellow he refused to debate, and he wrote a whole book about people he believed were heretics, titled, appropriately enough, Heretics. He disliked very few people—yet there were some.

Rufus Isaacs (aka Lord Reading) was one of those people. Chesterton disliked him for many reasons, including his political corruption and the lawsuit targeting Chesterton’s brother, Cecil.

A few critics sniff antisemitism behind this dislike. They note that Rufus Isaacs was Jewish, and Chesterton disliked him, therefore Chesterton must have disliked Isaacs because he was Jewish. Or worse, he must have disliked all Jews.

However, disliking a man who happens to be Jewish does not make one antisemitic. Chesterton himself reminds us what prejudice is: it is judging a person based on a characteristic of theirs before meeting them. This is what racists do. However, as Chesterton explains, if one dislikes a person after meeting them, it is no longer defined as prejudice—it is an opinion.

We would be wrong to generalize Chesterton’s dislike of Rufus Isaacs as prejudice against the Jews. Chesterton disliked Isaacs not because Isaacs was Jewish, but because Chesterton found Isaacs not to be a likable person.

Dates Matter

When reading Chesterton, especially his writings on the Jews, Hitler, and Nazism, the dates are critically important. Here’s a helpful timeline:

- 1874 – G.K. Chesterton is born

- 1914 – World War I begins

- 1918 – World War I ends

- 1922 – G.K. Chesterton converts to Catholicism

- This same year, he also publishes Eugenics and Other Evils, a prophetic book warning of the Nazi program of Eugenics. He wrote this a year before Hitler wrote Mein Kampf and long before the concentration camps.

- 1933 – Hitler opens first concentration camp (Dachau) primarily to hold German political prisoners

- 1936 – G.K. Chesterton dies

- 1938 – Jews are first rounded up and deported to concentration camps

- 1939 – Hitler invades Poland, beginning World War II

- 1941 – The Holocaust begins, initiating the murder of six millions Jews

Every single person today knows about the Holocaust. However, Chesterton didn’t know. He lived prior to World War II, and he was unaware of the atrocities that were yet to take place against the Jews. He had hints, and he criticized them, but he of course couldn’t have fully known what Hitler would do. Therefore, we shouldn’t view Chesterton’s writings through a post-Holocaust lens. (If Chesterton had lived through the Holocaust, we can be sure he would be among the strongest and most vocal opponents of the Nazi persecution.)

Many of Chesterton’s so-called “positive” statements about Hitler came from the 1930s, prior to the war and prior to the Holocaust. Chesterton’s approach to Hitler, as with any person, was to always give them the benefit of the doubt. This perhaps made him naive about Hitler in the 1930s, although he criticized Hitler strongly and repeatedly as it became clearer that Hitler was in a decline towards darkness. Still, Chesterton could not have known in 1936 the evil Hitler was planning. No one knew then.

It’s also worth noting that Chesterton, like most people, matured over time. His moral views changed and improved. Therefore, it’s wrong to simply pluck one line from one essay, and wave that in the air as evidence that Chesterton was hateful and racist. We must pause and ask questions such as, “What did he mean when he wrote that? What was his stage in life? Did Chesterton write this before or after his conversion to Catholicism? And what was the cultural context? Did he write that before or after Hitler came into power, before or after the Holocaust?”

Making this same point in his own defense of Chesterton, New York Times columnist Ross Douthat discourages the “chauvinism of hindsight”:

[B]y the standards of the '20s and '30s, it was morally impressive for a political writer to reject both fascism and communism, to praise Zionism, and to speak out forcefully against Nazi antisemitism [as Chesterton did]—and not in its eliminationist phase, but in its very earliest stages. . .

Here I think [Adam] Gopnik [a Chesterton critic] is indulging the chauvinism of hindsight: The assumption that everyone who partook of the attitudes that helped make the Holocaust possible should be judged and condemned on the basis of what we know now, rather than what they knew then. It's the Goldhagen approach to assigning culpability, in which even people who opposed Hitler—even people like Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who died fighting him—are to be judged, and harshly, if they failed to live up the standards that Western society only adopted after the Holocaust provided a terrible example of where these thoughts and impulses can lead.

Context Matters

Writing before the Holocaust, G.K. Chesterton was bound to be scrutinised through that lens, with every comment—and especially every joke—studied for its potential to lead to genocide: post hoc ergo propter hoc. It is claimed that Chesterton’s works “brimmed with antisemitism,” but Chesterton died before the Holocaust, and although calling someone “a product of his time” cannot excuse [apparent] antisemitism, a more complex picture emerges when they are studied in context.

— Ann Farmer, author of “Chesterton and the Jews: Friend, Critic, Defender”

As the saying goes, “A text without a context is a pretext.” Like the work of any author, we should read Chesterton’s writings in their original context. This includes, first of all, their historical context. We should study history and determine when Chesterton said what he said, per the section above.

In the end, if we go into Chesterton’s works determined to “find” bad things, if we have a pretext, then we will find bad things, for anything he wrote can be twisted or taken out of context, as with most writers and books—including the Bible. One cannot pluck passages from the Bible out of context, without any consideration for historical or literary context, and expect them to explain themselves in today’s terms. The same applies to Chesterton’s writing. Context matters.

Chesterton’s Virtue Matters

Any lines from Chesterton’s pen that seem, to modern readers, confusing—are they antisemitic or not?—should be interpreted in light of the overwhelming evidence of Chesterton’s virtue.

In a courtroom, character witnesses are often called forward to weigh in on the general character of the person being tried. This helps the judge and jury to interpret things the defendant has claimed. For what matters most is not what a person has said, but what they meant by their words—how they intended them. A study of a person’s character sheds light on their probable intention. If a person is known to be generally virtuous, it’s easier to assume their words had virtuous intent.

Consider G.K. Chesterton. Picture a scale in which, on one side, sat the small handful of apparently troubling words critics point to, and on the other side sat not just the millions of positive and virtuous words but also the staggering avalanche of testimony from friends, colleagues, readers, and even opponents of Chesterton (including many Jews), all almost universally attesting to his goodness and love for all people. Then ask yourself: which way does the scale tip? What’s the most likely interpretation of his words? For those who know him well, his virtuous character seems utterly incompatible with racism, which means any racist interpretation of his words is almost certainly the wrong one.

Chesterton Wasn’t Perfect

Saints are imperfect. They make mistakes. They sin and they know it. In fact, as Chesterton said, “There are saints indeed in my religion: but a saint only means a man who really knows he is a sinner.”

Chesterton was a sinner. This is widely admitted not only by those who love Chesterton, but by Chesterton himself who said the reason he became Catholic was “to get rid of my sins.”

Chesterton, a fellow sinner, was sometimes insensitive in his writings, not intending to be hurtful but nevertheless having that effect on some readers. And some of his writing stereotyped groups in unfair ways, such as the Germans, Russians, politicians, bankers, pacifists, or Jews. He was also naive, at least early on, about Hitler’s capacity for tremendous evil. Again, Chesterton wasn’t perfect.

However, none of those mistakes rose to the level of antisemitism. Chesterton may have been insensitive or wrong on occasion, like all of us, but he was emphatically not racist.

Cancel Culture is Wrong

Accusations of antisemitism are bad enough, as those charges are false and baseless. But the further attempt to cancel Chesterton’s whole life and legacy is even worse.

Today’s rabid cancel culture insists that a person is no better than the worst choice he has ever made, or the worst thing he has ever said. It demands total purity, by today’s standards, with zero tolerance for invincible ignorance, repentance, or moral improvement over time. This is, of course, completely unrealistic and naive, and it ignores the fact that every person is a mixed bag of virtue and vice. All people have made mistakes, and all people have areas where they can improve. This doesn’t make them evil; it makes them human.

Ask yourself: would you want to be reduced down to the worst choice you have ever made? Your most regretful opinion? The worst thing you ever said publicly? Is that what should ultimately define you? Is that the standard by which future generations should judge you?

Cancel culture is even worse when it targets people who can no longer defend themselves. G.K. Chesterton, as we all know, is dead. We can no longer ask him exactly what he meant by what he wrote, making him the perfect scapegoat for cancel culture since he can’t respond to any accusations. At times, we can determine what he meant from context, but other times we are left bewildered and would, indeed, like to ask him, “What did you mean by that?”

Of course, in light of his monumental virtue, fair readers give Chesterton the benefit of the doubt. We hope he might explain his words in another of his essays, or we ask his friends, those who have been reading and studying him for the past 30-40 years, those who know his voice well and understand his way of speaking, what they believe he meant. And we trust that those people know best his intent and meaning.

Cancel culture is toxic, unjust, irrational, and dangerous. It has no place in a healthy society and especially not among Christians, admitted sinners all in need of grace.

What Now?

There have been several unsettling accusations lodged against G.K. Chesterton, including charges of antisemitism. This FAQ does a commendable job in responding to these charges fairly. It is also important to remember to always view and judge historical figures within the contexts of their times, not ours. We owe great writers and critics like Chesterton interpretation, not cancellation.

— Rabbi Daniel Ross Goodman, Ph.D., The Jewish Theological Seminary of America, Postdoctoral Scholar at University of Salzburg, Department of Systematic Theology

Now that you’ve finished reading this detailed FAQ, what now?

Step #1 - Read Chesterton and decide for yourself.

We have nothing to hide. In fact, we’ve been working hard to make every last Chesterton text easily available online, including ones critics point to, through the Chesterton Digital Library.

This library will eventually contain all the books, essays, poems, reviews, and speeches that Chesterton ever wrote, tens of thousands of texts. We are not suppressing or hiding any of Chesterton’s works—we’re making them more available.

(Note that a number of essays don’t yet appear on the site because of copyright restrictions. For example, essays published after 1925 are not yet in the public domain.)

We especially encourage you to read articles that critics point to as evidence of Chesterton’s supposed antisemitism, so you can read his words yourself, in their full context. Again, we have absolutely nothing to hide. Here are scans of original texts mentioned in this FAQ:

- Chesterton’s 1918 open letter to Rufus Isaacs (Lord Reading)

- G.K’s Weekly

- “The Judaism of Hitler” (July 20, 1933)

- “The Tool” (September 6, 1934)

- “A Queer Choice” (November 29, 1934)

- “On War Books” (October 10, 1935)

- “Why Did He Do It?” (March 26, 1936)

Step #2 - Learn more about this issue.

If you would like to go deeper on the issue of Chesterton and the Jews, we encourage you to read this 59-page issue of Gilbert magazine (PDF) from 2008, which contains several in-depth articles.

You might also download The Chesterton Review Index (PDF) and search for “antisemitism” to read the numerous scholarly works written on the topic (a subscription is required to read those articles).

We especially recommend Ann Farmer’s exhaustive 530-page book, Chesterton and the Jews: Friend, Critic, Defender. We do not claim this is the definitive book on Chesterton and the Jews. It is but one study. We continue to learn more every day, and more books and articles will certainly be published. But Farmer’s book is by far the most comprehensive and well-balanced study to date. It offers a careful and detailed look at the question, examining all the evidence and, most importantly, placing it in context.

Step #3 - Listen to former antisemites who were converted by Chesterton.

We are unaware of a single person who has become antisemitic as a result of G.K. Chesterton’s writings. However, we do know of several former antisemites who dropped their racial prejudices after reading Chesterton, including Joseph Pearce and Stuart McCullough.

McCullough shared his experience via email:

Are G.K. Chesterton’s writings full of antisemitism? Some people claim so, after reading a few lines plucked by his critics.

However, I think I have an advantage when considering this subject because during the late 1980s and early 1990s, I was extremely antisemitic. During that time I was involved in what would be called extreme right-wing, white supremacist, or antisemitic political groups.

I started reading Chesterton at this time in part because I had heard rumours that he shared my antisemitism. But I was extremely disappointed. Although I enjoyed his writings on politics, morals, economics, history, and even some of his fiction, I didn’t find the antisemitism I was looking for, no support for my racial beliefs.

In fact, the more I read Chesterton, the further I moved away from antisemitism. He helped me see the evils of racism. Eventually, he led me all the way into the Catholic Church, helping me develop a greater understanding of the world’s real problems.

So, when people read Chesterton and think they see antisemitism, they should bear in mind that I, as a former antisemitic activist, can say that I found none.

McCullough not only abandoned his antisemitism after reading Chesterton but went on to found the Catholic G.K. Chesterton Society in England. Hear his full story in this recent video interview with McCullough.

Step #4 - Debate us!

We would be happy to debate anyone on a point-by-point basis who still believes, after reading and study, that Chesterton was antisemitic. We have nothing to hide or fear. If you would like to set up a debate on this issue, please email [email protected].

We are convinced that G.K. Chesterton was not antisemitic. He was not racist. He detested racism and was an ardent opponent of racial theories, including antisemitism. He fought for human dignity and affirmed the brotherhood of all men.

That’s the true character of G.K. Chesterton.

About the Authors

Brandon Vogt

Brandon Vogt is a bestselling author of ten books and the founder of ClaritasU. He works as the Senior Publishing Director for Bishop Robert Barron’s Word on Fire Catholic Ministries.

He is the founder of Chesterton Academy of Orlando, a classical high school grounded in the Catholic faith, and serves as President of the Central Florida Chesterton Society. He lives with his wife and eight children on Burrowshire, a small farm outside of Orlando.

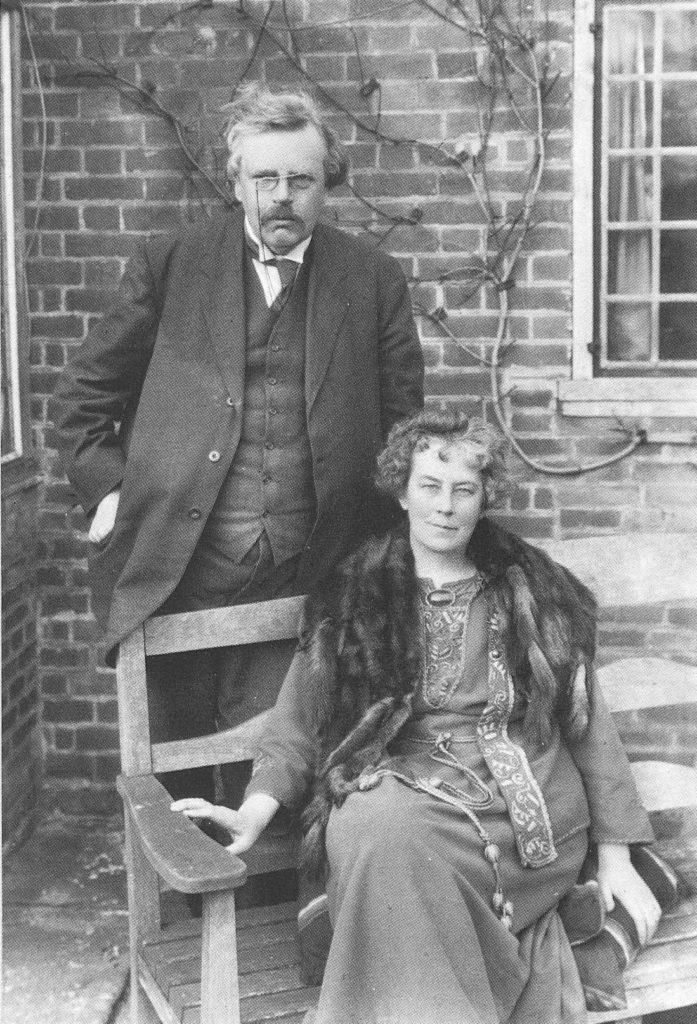

Nancy Carpentier Brown

Nancy Carpentier Brown works as Director of Communications for the Society of G.K. Chesterton. She is the author of numerous Chestertonian titles, including: The Father Brown Reader: Stories from Chesterton, The Father Brown Reader II: More Stories from Chesterton, Chesterton’s The Blue Cross: Study Edition, and A Study Guide for G. K. Chesterton’s St. Francis of Assisi. She also wrote the first biography of G.K. Chesterton’s wife, Frances Chesterton, titled The Woman who Was Chesterton.