“Chesterton and My Jewish/Catholic Journey”

A Response to Dawn Eden Goldstein

Brandon Vogt and Nancy Carpentier Brown

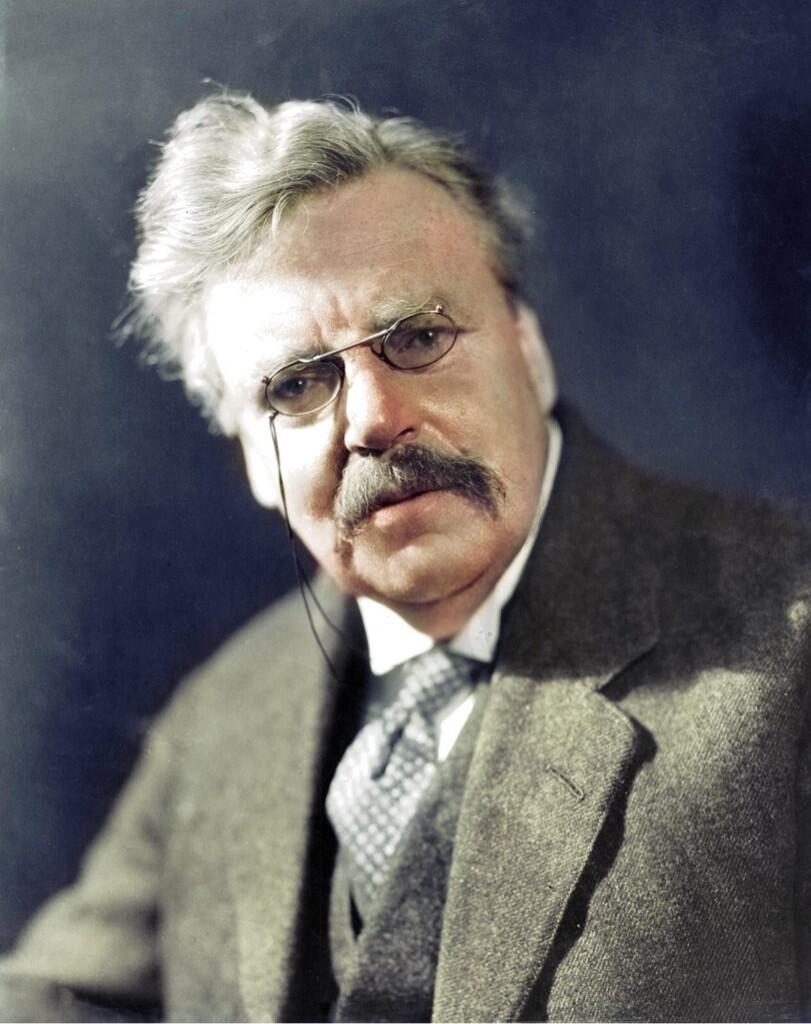

Dawn Eden Goldstein was invited to speak at the 40th Annual Society of G.K. Chesterton Conference on July 30, 2021 about the role Chesterton played in her spiritual journey, as a Jewish convert to Catholicism.

During the talk, Goldstein praised Chesterton for many things but also accused him of antisemitism and racial prejudice, sins for which she called the Chesterton community to repent.

Below you will find a full transcript of her talk with responses from the Society of G.K. Chesterton.

We have also linked to each of the Chesterton texts Goldstein mentions in her talk, so you can read the quotes offered by Goldstein in their full, original context.

(For more on this topic, please see our in-depth Chesterton and the Jews FAQ.

Introduction

Thank you all so much. Let me just point the microphone a bit. They told me not to lean into it, so hopefully you can all hear me. What a joy it is to be here. I’m very grateful to the Society of G.K. Chesterton for giving me this opportunity to discuss “Chesterton and My Jewish/Catholic Journey.” When Dale—where is he?—he’s motoring around here. There he is. I told him that now that he’s motoring around and he has the goatee, we need to have some one of our artists here paint the back of his jacket saying Heaven’s Angels.

So when Dale Ahlquist called to invite me to speak on my experience as a convert to Catholicism from Judaism, whose journey into the Church was sparked by reading Chesterton, I told him in all honesty, that I wrestled with Chesterton’s writings on Jews. Dale encouraged me to speak honestly about that wrestling, and I am grateful for it.

And we’re grateful for Goldstein wrestling with this question! It does seem to be a recent struggle, however. Goldstein converted to Catholicism in 2006. The following year, she gave a talk at the 2007 Chesterton Conference entitled, “The Girl Who Was Thirsty: How G.K. Chesterton Opened the Door to My Conversion.” Goldstein did not mention at the time that she had struggled with any of Chesterton’s writings on the Jews.

I know from experience that the Chesterton community is not afraid to reckon honestly with uncomfortable truths. In fact, it was that very honesty within the Chesterton community that helped me overcome my resistance to entering the Catholic Church.

In 2002, when I was a new Christian, but before I was Catholic, I was one of the only Protestant members of the New York City Chesterton Society. I was just wondering, is there anyone here, whether you’re now still Protestant or whether you’re Catholic now, is there anyone here who’s known that experience of being one of the only Protestants in a Chesterton Society? Yes, yes, well, God bless you, thank you for your persistence.

So, I remember that there was a meeting when we were discussing Chesterton’s writings on the need to acknowledge one’s sins, and I said, “Well,” remember this is 2002, I said, “Well, it doesn’t seem like the Catholic Church is in line with what Chesterton’s saying because when I pick up the newspaper I see Catholics denying that their Church has a problem with priests who abuse children. They’re saying that the problem isn’t with the priests but with the media exposing the priests. That doesn’t seem to me like a willingness to acknowledge sins.”

To my surprise the Catholic members of the group answered by saying that whatever I might have read in the newspaper about Catholics being defensive on the abuse issue, they weren’t defensive. They were as angry about abuse in the Catholic Church as I was. In fact, they were even angrier. They were willing to admit that their own Church had a problem and they themselves wanted to be part of the solution to that problem.

That meeting was a revelation to me. I had no idea that there were people who were sincere faithful Catholics who were willing to admit that the Church they loved, the Church they were willing to die for, was in need of purification. It was the witness of those Catholics, my fellow admirers of G.K. Chesterton, that helped me believe that I could be part of the Catholic Church, the Church that is at one and the same time a school for saints and a hospital for sinners.

So, I intend to speak about Chesterton’s role in my conversion and then to address some of the writings of his that I have wrestled with.

But before I do that, I have some preliminary reflections on the topic of what we should do when someone we admire does something that gives us pause or that should give us pause. As some of you may know, and as I just learned from Dale Ahlquist, there’s a book that’s coming out in England by Richard Ingrams called, The Sins of G.K. Chesterton. And from what Dale has told me, based on an excerpt that’s been published from this book thus far, it’s going to be a book that will be a challenge to the Chesterton community.

See our review of Ingrams’ book here. This book is not a serious challenge to the Chesterton community. Ingrams’ accusations are neither new nor convincing. Rather than focusing on Chesterton himself, most of the book impugns Chesterton’s brother (Cecil), sister-in-law (Ada), and close friend (Hilaire Belloc) for racist views, and then tries to condemn Chesterton for his association with those people.

And so this makes even more important I believe what we read in the First Letter of Peter in the translation by Chesterton’s friend, Monsignor Ronald Knox, “The time is ripe for judgment to begin and to begin with God’s own household. And if our turn comes first, what will be its issue for those who refuse credence to God’s message?”

G.K. Chesterton lived this truth. He wrote in his autobiography, “When people ask me or indeed anybody else, why did you join the Church of Rome? The first essential answer, if it is partly an elliptical answer, is to get rid of my sins.” With those words, Chesterton gives us a moral imperative. If those of us who are Catholic are to imitate him, we must be willing to undergo a purification, a reckoning.

Since the world became aware of the horrors of Nazi Germany, many communities of people who admire certain great artists or writers have gone through a reckoning of their own.

To give one example, out of many, the great composer Richard Wagner, a genius whose operas are justly celebrated. But he was also a fierce nationalist and antisemite, whose creative works became an inspiration to Adolf Hitler.

Although it would be wrong to implicate Wagner in the Holocaust, his works are so inextricably associated with Hitler that today, if people wish to perpetuate his music, they must engage in frank discussion about his offensive views. That is to say, Wagner’s fans must face his offensive views honestly. They must distinguish between those things he said that are worthy of praise and those things he said that are unacceptable.

That is the only way to ensure that Wagner’s true legacy, his artistic greatness, will endure for future generations.

It seems Goldstein is suggesting that Wagner’s legacy will only endure if fans acknowledge his offensive views and separate them from his praiseworthy words and music. We agree. Thus far, however, Goldstein has not called fans of Wagner to do penance or undergo any kind of purification or penitential acts, things she encourages of Chesterton fans.

And that kind of reckoning is in fact what many Wagner fans are doing throughout the world. Our friend Joseph Pearce has pointed out that J.R.R. Tolkien, who fiercely defended Jews and opposed Hitler, engaged in this kind of reckoning. Tolkien admired Wagner, yet he knew what to take of him and what to leave.

J.R.R. Tolkien, indeed, fiercely defended Jews and opposed Hitler. Yet so did G.K. Chesterton. The difference is that Chesterton died in 1936, several years before World War II and the Holocaust, and he denounced Hitler long before his Final Solution. Tolkien, on the other hand, lived until 1973—36 years after Chesterton’s death—and was most forceful in his criticisms only after the war had ended. If we praise Tolkien for denouncing the evils of Hitler, we should surely praise Chesterton for the same, and for doing it much earlier.

So too did Dietrich von Hildebrand, whose parents were personal friends of Wagner. We need that kind of reckoning in the Chesterton community to ensure likewise that Chesterton’s true legacy, his true greatness, endures as it should.

We’re grateful that Goldstein recognizes Chesterton’s “true greatness” and that she agrees his legacy is worth preserving. However, she seems to be under the impression that she is raising these questions for the first time, that there has been no serious reflection within the Chesterton community on Chesterton’s views about the Jews. She suggests now is finally the moment for those discussions.

However, since 1901, when Chesterton first became popular in England, these kinds of discussions have been taking place. Furthermore, the charge of antisemitism, which Goldstein focuses on in this talk, was made during Chesterton’s own lifetime, a charge he vigorously denied. It’s nothing new or surprising.

Rather than ignoring the charge, over the last several decades the Society of G.K. Chesterton has published numerous articles and even whole issues of our magazine addressing this accusation.

The implication that Chesterton’s faults have only now come to light resonates only in the minds of people who are discovering these things recently, for the first time.

And here I think again of Dietrich von Hildebrand as an example, and I want to tell you a story that I heard from his widow, Alice von Hildebrand. Alice von Hildebrand says that Dietrich told her that if after his death she found anything in his writings that was against the teachings of the Catholic Church, she was to burn them. Is there anybody here who does not believe that G.K. Chesterton would have said the same thing?

This of course presumes Chesterton’s writings about the Jews were “against the teachings of the Catholic Church.” Yet we deny that’s the case. Goldstein has not proved this, as we explain in our replies. We believe Chesterton was charitable and sympathetic to the Jews even in his criticisms.

Also, we don’t necessarily believe a writer’s work should be burned simply because some people might misunderstand or misinterpret parts of it after his death. An author’s work should be freely available to all. If there are passages that appear troubling, we should strive to understand the context of those passages and what the author truly intended to convey. We must remember that Chesterton’s goal — as stated in the Summary of The Everlasting Man — was evangelization, and he sought to bring all souls to Christ.

(This reply was revised in March, 2024, in response to a request from Goldstein.)

Is there anyone here who believes that Chesterton would want people to follow his example if he did or wrote or said something contrary to Catholic teaching? No, absolutely not.

We agree! Goldstein is certainly right on this point.

G.K. Chesterton strove in every way to be a man of the Church. When he was wrong and realized he was wrong, he confessed his sins and sought to amend his life. That is why we have the famous story that when The Times asked readers to tell them what was wrong with the world, Chesterton wrote, “Dear sir, I am. Yours, G.K Chesterton.”

Now I know from the Quotemeister on the Society of G.K. Chesterton’s website that that quote may not be authentic, we don’t know. But regardless of whether it is authentic or is merely a legend, it has survived because it expresses the deepest truth about who Chesterton was and who he wanted to be.

We agree here, too! There has been no time in the last 120 years when Chesterton readers have claimed that he was perfect and said no wrong. Chesterton made mistakes, which we freely acknowledge. For example, his work occasionally contained sentences that were imperfect, unclear, insensitive, historically inaccurate, or could be perceived as offensive. Chesterton knew this himself. He identified as a sinner and went to confession. He was imperfect.

So, we should not be afraid to engage in an honest reckoning with Chesterton’s writings on Jews because Chesterton himself would want us to do so.

Again, we agree. Chesterton himself encouraged people to engage his writings on the Jews. He said so during his own lifetime. But the implication that Chesterton fans have resisted such engagement is not true.

Chesterton's Imperatives

I want to speak now about what it was like for me, as someone from a Jewish background to encounter Chesterton. First, I must be honest with you, if you think of a Jewish home as a home that keeps Kosher and where men wear yarmulkes, that was not my home. My family practiced and largely still practices, Reform Judaism, which is the liberal Jewish tradition that arose in Germany during the 19th century and is the dominant form of Judaism in the United States. With that said, I did know my Jewish faith, I did know it. I went to Jewish Sunday School as a child. And when I was 13, I was a Bat Mitzvah, meaning that I took a leading role at a coming of age ceremony where I read from the Torah.

During my high school years, I drifted away from my Jewish faith. By the time I entered college, at New York University, my religion was rock and roll. It was the mid-1980s and I was a contrarian, some things never change, so I fell in love with the music of my parent’s generation and became a historian of the pop music of the 1960s. I wrote for rock history magazines, such as Mojo, and I interviewed great artists such as Brian Wilson, Lesley Gore, Harry Nilsson, and Del Shannon.

It was a rock musician who first introduced me to Chesterton. I was interviewing him and asked him what he was reading lately and he answered, “The Man Who Was Thursday.” That was December 1995. I was 27 years old, which makes me now 50 [sic]. And I went out almost immediately and bought The Man Who Was Thursday. When I finished reading it, I went on to read Orthodoxy and Heretics. Four years and many more Chesterton books later—I was a Protestant and in 2006—thanks be to God, I entered into full communion with the Catholic Church.

What attracted me to Chesterton? I was drawn to him because I could see that there was something timeless about him. He seemed to me to be, as the title of this conference says, Chesterton seemed to me to be a prophet.

Writing at the start of the 20th century, he foresaw the coming of what Pope Benedict XVI would call “the dictatorship of relativism.” It was a world that was very familiar to me, yet I knew that it was not making me happy. Chesterton, by contrast, and this also gets to the title of this conference, Chesterton by contrast was joyful. When I read him, I knew he had something I wanted, and as I read more deeply into his writings, I drew from him certain moral imperatives. These imperatives came to shape my personal worldview and they still shape me today. They are as follows:

1) I must always place language at the service of truth. Chesterton wrote:

“I know nothing so contemptible as a mere paradox; a mere ingenious defense of the indefensible. If it were true (as has been said) that Mr. Bernard Shaw lived upon paradox, then he ought to be a mere common millionaire; for a man of his mental activity could invent a sophistry every six minutes. It is as easy as lying; because it is lying. The truth is, of course, that Mr. Shaw is cruelly hampered by the fact that he cannot tell any lie unless he thinks it is the truth. I find myself under the same intolerable bondage. I never in my life said anything merely because I thought it funny.”

Chesterton did, however, use humor at the service of truth. A critic once complained to him, “If you must make jokes, at least you need not make them on such serious subjects.” Chesterton replied with a natural simplicity and wonder, “About what other subjects can one make jokes except serious subjects?” He added, “Men talk for hours with the faces of a college of cardinals about things like golf, or tobacco, or waistcoats, or party politics. But all the most grave and dreadful things in the world are the oldest jokes in the world—being married; being hanged.”

Another critic, Joseph McCabe, claimed that Chesterton was not serious but only funny, because McCabe thought that funny was the opposite of serious. But as Chesterton responded, “Funny is the opposite of not funny, and of nothing else.”

2) I must always place personal judgment at the service of truth. I read in Chesterton:

“Pride consists in a man making his personality the only test, instead of making the truth the test. It is not pride to wish to do well, or even to look well, according to a real test. It is pride to think that a thing looks ill, because it does not look like something characteristic of oneself.”

We agree with the principle, but wonder whether Goldstein has followed this imperative in her assessment of Chesterton’s work. It seems that Goldstein, throughout this talk, concludes that some of Chesterton’s views are ill because they are not characteristic of Goldstein, a twenty-first century modern.

3) I must call out sin for what it is. I read in Chesterton that Original Sin is “the only part of Christian theology which can really be proved.” And, “When people ask me or indeed anybody else”—that’s the quote I read earlier—”why did you join the Church of Rome?” Chesterton’s answer was, “To get rid of my sins.”

Nowhere does Chesterton say, “You must call out sin for what it is.” Chesterton says he became Catholic, “To get rid of my sins,” not “To better identify and call out other people’s sins.” Indeed, we must root out our own sins and seek forgiveness from God. But we’re unsure where Goldstein derived the imperative to root out and publicly condemn the personal sins of others. That’s not a Chestertonian imperative.

4) God gave me the gift of reason—I must use it. Chesterton wrote, “There is a thought that stops thought. That is the only thought that ought to be stopped. That is the ultimate evil against which all religious authority was aimed.”

The quote Goldstein cites here is from Chesterton’s book Orthodoxy and is in reference to self-annihilation. Chesterton is lamenting those who are so skeptical that they conclude, “I have no right to think for myself. I have no right to think at all.” Certainly this is not descriptive of the Chesterton community. We agree that reason is a gift and we are right to use it.

However, reason stands staunchly opposed to bias. Reasonable people consider and evaluate multiple views about a topic—not just one. But the works cited in Goldstein’s talk are few and mainly come from one self-published author and blogger named Simon Mayers. A truly reasonable approach to this topic would include a much wider variety of voices and viewpoints, especially those who do not agree with Goldstein’s and Mayers’ conclusions.

5) I must recognize and follow permanent standards of morality. I read in Chesterton:

“We often hear it said, for instance, ‘What is right in one age is wrong in another.’ . . . If the standard changes, how can there be improvement, which implies a standard? . . . The theory of a complete change of standards in human history does not merely deprive us of the pleasure of honouring our fathers; it deprives us even of the more modern and aristocratic pleasure of despising them.”

We, of course, agree with Chesterton that there are timeless standards of morality. Rules such as “You must not murder” and “You must not unjustly discriminate against people” are forever binding, even if throughout history various cultures or people have been confused (or wrong) about those rules.

However, although we’ve been given timeless standards of morality, there are not timeless linguistic or stylistic standards. The latter change, and change often. For instance, it’s a timeless moral standard that “You should not be racist,” but what counts as being truly racist has shifted from century to century. In Chesterton’s day, making a light joke about the Irish, or even a self-deprecating joke about the English, was not considered racist. In our more sensitive twenty-first century, it might. The rule against racism is unchanged, but the conventions about what qualifies as racism have shifted.

Chesterton, per usual, understood all of this. He summed it up succinctly when he advised us to “Break the conventions and keep the commandments.”

6) Being Christian means resisting evil within myself and within society. I read in Chesterton, “A dead thing can go with the stream, but only a living thing can go against it.” And, “[I]f the divinity is true it is certainly terribly revolutionary. . . Christianity alone has felt that God, to be wholly God, must have been a rebel as well as a king. Alone of all creeds, Christianity has added courage to the virtues of the Creator.”

Once again, we agree with Chesterton’s principles, but none of those principles seem to support Goldstein’s attack on Chesterton. Criticizing Chesterton as racist does not require much courage in light of the current tendency to attack historic thinkers using the standards of today. Political incorrectness is usually not evil, but it is certainly easy to identify and attack, especially when the victim is dead and unable to respond.

What requires true courage today is to stand up and defend such people against misguided accusations of racism, assuming such people are indeed innocent of those charges.

Sources on Chesterton

Now with those moral imperatives in mind, I would like now to examine some representative samples of Chesterton’s writings on Jews. There is only time to look at a few examples. For more, I would refer you to Simon Mayers’ excellent study, Chesterton’s Jews.

We have read Simon Mayers’ book and found it underwhelming. Mayers is an independent writer and blogger who self-published a short book on Amazon titled Chesterton’s Jews: Stereotypes and Caricatures in the Literature and Journalism of G.K. Chesterton.

The book is lacking in serious scholarship. It is full of inaccuracies and bias, and was generally dismissed by the scholarly community. In fact, only one scholarly review has ever been written about it. That review, published in the Journal for the Study of Antisemitism, said:

“Chesterton’s Jews reads as an activist response. . . As a work of scholarship, however, while offering promise in its central argument, the volume suffers from its activist tone and lack of development in the areas of historical contextualization, nuanced distinctions, and questions asked.”

One main reason for this poor assessment is that Mayers engages in heavy proof texting. Proof texting is the practice of plucking quotes from a document, usually for the purpose of supporting a predetermined point, one shaped by the prooftexter’s own presuppositions, biases, or agenda. Prooftexters ignore the full context of these quotes, which more clearly reflect the author’s intended meaning, and they rarely include alternative sources that paint a more balanced picture of the topic. This is the case with Simon Mayers’ book, and it’s why the Journal for the Study of Antisemitism panned it.

Further, Mayers’ book was published in 2013, long after Goldstein’s conversion in 2006. And it seems Goldstein has only recently discovered the book. What Goldstein fails to realize is that these accusations, which she just recently discovered through Mayers book, have been known and discussed for the past 120 years. As we’ve noted, Chesterton was accused of antisemitism in his own lifetime—and vigorously denied it. Since his death, there have been numerous papers, articles, magazines, and books—thousands of pages—discussing and analyzing Chesterton’s views of the Jews. Goldstein is not a pioneer in this respect, and her failure to acknowledge this is one of the greatest faults of her talk, which is not scholarly as it neglects to recognize all previous work in this area other than Simon Mayers’ thin self-published book.

I need to tell you that some of these writings may be shocking to you. They were shocking to me when I read them.

We grant that they may have been shocking to Goldstein, but these writings are not shocking to those who have read much of Chesterton, especially those who know his views and unique style of writing. His use of satire is not surprising. What Goldstein interprets as flippancy toward the situation of Jews would be described by Chesterton as a satirical description of serious subject matter in order to bring forth the truth.

I actually, after reading some of these, I ordered from the library G.K.’s Weekly to look at one of the articles mentioned in Simon Mayers’ book in context so that I could see how it looked on the paper. I wanted to see that these things weren’t being just taken out of context and twisted.

If Goldstein were trying to make a serious attempt at studying this issue, she would need to do more than just track down the individual essay from which Mayers plucked his quotes. She would look at other columns produced by Chesterton at the time, columns just before and just after the essay in question, and learn more about the events and characters which inspired those columns. She would also read newspapers Chesterton read at the time to see what others were saying, in order to contextualize his quotes within the cultural conversation.

Neither Goldstein nor Mayers took this initiative but it’s the sort of hard work that other scholars have done, such as Ann Farmer in her book Chesterton and the Jews: Friend, Critic, Defender, which is a far more serious, careful, and balanced volume than Mayers’ slim book (and at 530 pages, more than four times longer than Mayers’ book.)

And what I found was that they weren’t [taken out of context], and what I found also was that there was one essay of Chesterton’s which we’re going to look at here where he said something that was so disturbing that when Frank Sheed collected his writings, it was excised.

Here we must point out that the words “disturbing” and “excised” are Goldstein’s own judgments, assumptions. We do not know why the sentence was taken out.

As we’ll see, on Goldstein’s view, Sheed found the sentence so offensive and antisemitic that he removed it. But we do not know this is the case. Frank Sheed, being a good editor, likely removed this sentence because he sensed that it might be open to being misinterpreted, just exactly as it has been here by Goldstein.

And the version of this essay of Chesterton’s called “On War Books”, that’ll be the last example we’ll look at. The version that is in the Ignatius [Press] Complete Writings of Chesterton [note: actually Collected Works of G.K. Chesterton] is the Frank Sheed version that excises this one line. So, I mentioned this because it’s all the more reason why we as the Chesterton community need to get ahead of things like this book that’s coming out from Richard Ingrams.

Goldstein is suggesting here that by condemning Chesterton’s supposed antisemitism ourselves, as the Chesterton community, we’ll “get ahead” of claims about to be made in a book that was yet to be published at that point in time. Almost the only thing known about Richard Ingrams’ book was its title, The Sins of G.K. Chesterton.

However, the Chesterton community isn’t interested in PR strategy. We’re not concerned with “getting ahead” of critics. We’re interested in the truth, and the Chesterton community has been telling the truth about G.K. Chesterton for over 40 years.

We have not hidden any part of Chesterton’s writings. In fact, for the past two decades, we’ve worked diligently on a digital collection of all his works, not suppressing anything, not hiding anything, working to present every single piece of writing in its original form as it was originally published. These are not the actions of an organization attempting to hide anything.

(After Richard Ingrams’s book was published, we read it carefully and reviewed it here. Notably, the book did not include a single reference to the sentence Goldstein believes is antisemitic.)

We need to read Chesterton’s Jews by Simon Mayers which has quite a lot more information than in the Ann Farmer book [Chesterton and the Jews] . . .

The thin Mayers book, at 125 pages, compared to the thick Farmer book, at 530 pages, cannot by any means be said to have “quite a lot more information.”

As noted above, the Mayers’ book was self-published on Amazon and garnered but one scholarly review, in the Journal for the Study of Antisemitism. The review harshly criticized Mayers’ book as “an activist response,” one that “suffers from its activist tone and lack of development in the areas of historical contextualization, nuanced distinctions, and questions asked.” The review also noted Mayers’ failure to address the issue of why Chesterton is so regularly defended against the charge of antisemitism.

If a scholarly journal devoted to the study of antisemitism dismissed the Mayers book as unscholarly and agenda-driven, then it is simply a poor tool to use against Chesterton. Goldstein gives this book far too much weight and leaves out many other studies which should have been referenced in her talk.

. . . and we need to know what he [Chesterton] said so that we can know what to take or leave and how to reckon within ourselves so that when people come back to him and say, “Do you know that Chesterton said that?” Instead of saying, “Oh, that’s a lie. I have the Ignatius edition of Chesterton and he never said that,” we can say, “Yes, we know that he said it, it was so terrible that it was left out of his collected edition and it was wrong and we don’t believe that and we believe that if Chesterton were alive today he would disavow that because Chesterton, at his best and in the deepest recesses of his heart, always stood for what was true.”

This is a straw man. We’re unaware of anyone who has ever responded to quotes from Chesterton by saying, “Oh, that’s a lie; he never said that.” The Chesterton fans we know, if asked about a confusing or objectionable line in Chesterton, would not immediately accuse the other person of lying. Most would ask, “Really? That’s interesting. I hadn’t heard that line before. Where did he say that? And I wonder what he meant by it?” They wouldn’t immediately jump to the conclusion that the critic must be lying, that the critic must have fabricated a fake quote in order to attack Chesterton. By suggesting this is the case, Goldstein attempts to paint those who disagree with her as surreptitious cultists, eager to cover up anything objectionable their founder has ever said. But as we’ve seen, that is simply untrue for the Chesterton community.

Also note how Goldstein “poisons the well,” a common rhetorical tactic used by those padding a weak argument. Even before reading aloud the actual Chesterton line that she finds offensive, Goldstein has already deemed it “disturbing,” “terrible,” and “wrong,” and says its a line that good-hearted Chesterton fans would surely “disavow” along with Chesterton himself were he alive today. At this point in Goldstein’s talk, we haven’t even heard the line yet! Nevertheless, she has already gone to great lengths to bias the audience against it, in favor of her critical interpretation.

Poisoning the well might be an effective rhetorical tactic, but it’s not helpful in the pursuit of truth.

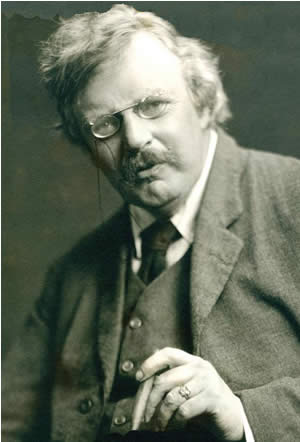

Chesterton on Israel Zangwill

So with that in mind, this picture [projected on the screen] is of Chesterton with Israel Zangwill, the Jewish poet. We read in Ann Farmer about Chesterton’s friendship with Israel Zangwill, [a friendship] that’s been used as something where we say, “See, Chesterton had Jewish friends.” What we don’t know about this, because it’s never been discussed, and it should be discussed with Chesterton community is that that photo was taken in 1909. I’m very sorry to tell you this, and I did not know until I read this [in Mayers’ book], but by 1924, Zangwill was saying that Chesterton was an antisemite and he was complaining that Chesterton and Belloc are constantly bragging about their Jewish friends. Now, we need to know this so that again when people tell us this we won’t say that’s a lie, we can’t say that because we stand for the truth. So, we have to say that we read that and we are concerned as other people are concerned and that doesn’t in any way negate the enormous good that Chesterton did. We acknowledge the bad but it’s necessary to do that in order to ensure that the good survives.

Again, Goldstein is suggesting that Chesterton fans would respond to this news by accusing the messenger of lying. This is unfair and untrue. It’s a straw man.

Goldstein also claims that we, the Chesterton community, “don’t know” about the true relationship between Chesterton and Zangwill. This is also untrue. Veteran Chestertonians know all about it. Ann Farmer’s book on Chesterton, for example, mentions Zangwill over 40 times (compared to only 17 in Mayers’ book, Goldstein’s primary source).

It’s indeed true that later in his life Zangwill cooled in his friendship with Chesterton and believed Chesterton was guilty of antisemitic views. But this opinion alone doesn’t mean that Chesterton was, in fact, antisemitic. There were many other Jews who held the opposite view about Chesterton. A year after Chesterton’s death, Rabbi Stephen Wise, President of the American Jewish Congress and the most important American Jewish leader in the 1930’s and 40’s, celebrated Chesterton, saying:

“Indeed, I was a warm admirer of Gilbert Chesterton. Apart from his delightful art and his genius in many directions, he was, as you know, a great religionist . . . I deeply respected him. When Hitlerism came, he was one of the first to speak out with all the directness and frankness of a great and unabashed spirit. Blessing to his memory!”

It’s not hard to find people with differing opinions about a public figure. However, if we’re interested in the truth, the question is not what this or that Jewish figure believed about Chesterton but whether he actually was or was not antisemitic. And for this we have to read his writings and discern their meaning. There’s no shortcut. We can’t just line up his critics on one side and his supporters on the other and see which group is larger or more prominent.

Chesterton on Henry Ford

So, first, let’s look at Chesterton’s thought on Henry Ford. When Chesterton went to America for his lecture tour in 1921, Henry Ford was publishing The Dearborn Independent, which was a newspaper that was at every Ford dealership and it was put in every Ford that was sold. And this newspaper was an outlet for Henry Ford to have all these stories about what he considered an International Jewish Conspiracy. And so that’s [on the screen] an example of the front page of The Dearborn Independent.

Here’s what Chesterton wrote on Henry Ford. He said, “Americans are accustomed to a cosmopolitan citizenship, in which men of all bloods mingle and in which men of all creeds are counted equal.”

Now this is very interesting, it seems Chesterton was unaware of segregation, unaware of signs saying, “No Irish Need Apply.” There’s something there that is not the Chesterton we know, it’s not the Chesterton who’s in service to truth or using his reason. It’s a blind spot and we need to acknowledge that.

Goldstein continues her string of unfair accusations, suggesting that during his American visit in 1921, Chesterton served something other than truth (a euphemism for lying) or had abandoned his reason (a euphemism for insanity).

She criticizes Chesterton for being unaware during his American visit of signs saying “No Irish Need Apply.” Yet this was almost certainly because he saw no such signs. Scholars have determined that the use of these signs has been wildly exaggerated in the popular imagination. Researchers combed through job postings over a six decade span, from 1842 to 1903, and found only a small handful of instances, an average of one posting per year across the entire country. And even those scant examples stopped in the early 1900s, decades before Chesterton’s visit to America in 1921. In other words, this was a mostly non-existent problem during Chesterton’s trip, and that explains why he didn’t comment on it.

Regarding segregation, it’s true that we don’t have any record of Chesterton condemning racial segregation during his 1921 trip to America. But is it fair to conclude that therefore he was racist, or had stopped “serving the truth or using his reason”? How many other writers, lecturers, and dignitaries visited America during the 1920s without commenting on segregation? Were they all racist, too?

Also, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Chesterton may very well have said something about segregation for which we have no record.

In any case, determining a hundred years later what someone should have said at a certain time and place, especially with the benefit of hindsight, is unfair at best.

That said, we do have plenty of evidence of Chesterton condemning the treatment of Blacks in America. He decried the lynchings that were taking place in the American South, calling it a real blot on America, a country which he otherwise admired in many ways because of its democratic spirit.

In his book, What I Saw in America, which contained reflections on that 1921 visit to America, Chesterton noted how, “White men have behaved like white devils to black men.” He added, “I believe… that the enslavement and importation of negroes had been the crime and catastrophe of American history.” He found it incredible that in America there really was a race war, where people hated each other for no other reason than skin color.

[Chesterton] goes on saying of Americans, “In a word, they are the very last men in the world who would seem likely to pride themselves on a prejudice against the Jews.”

Here Chesterton is not defending antisemitic Americans. He’s explaining how American antisemitism was latent and hidden, and not visible and open as it was in Europe.

For instance, in Germany antisemitism began spreading openly with a mark of pride, while in America it was evident but not broadcast widely.

Chesterton’s point was that it made sense that Americans did not pride themselves on being prejudiced given the country’s commitment to diversity, as the melting pot of the world.

And he and he goes on, I’m going to skip ahead, and he says, “Mr. [Henry] Ford,” let’s see, next slide, “Mr. Ford is a pure product of this pacific world as was sufficiently proved by his pacifism. If a man of that sort has discovered that there is a Jewish problem, it is because there is a Jewish problem. It is certainly not because there is an anti-Jewish prejudice, for if there had been any amount of such racial and religious prejudice, he would have been about the very last sort of man to have it.”

Here Chesterton is explaining his surprise at Henry Ford’s antisemitism. Ford is an American pacifist, and those two traits together, Ford’s citizenship in the tolerant and diverse America and his commitment to peace toward all men, make Ford one of the last people you would expect to harbor prejudice toward people of another race, such as the Jews. Chesterton is saying that if someone like that, an American pacifist, has recognized a “Jewish problem,” we should take serious note of it.

But what does Chesterton mean by “a Jewish problem”? Goldstein tosses off that phrase a few times during her talk but unfortunately never explains it. But it’s a critical phrase when trying to understand Chesterton’s writings on the Jews.

When read out of context, and in a post-Holocaust age, the “Jewish problem” sounds like something Hitler might have complained about. After all, Hitler offered his Final Solution to his perceived Jewish problem.

However, when writing about “the Jewish problem”—better called “the Jewish question”—Chesterton wasn’t implying that the Jews were a problem, as Hitler believed, but that they had a problem, namely that they were a nation without a country. They lacked a homeland. And Chesterton wanted to help them solve that problem, which is why, with support from Jewish friends, he became an ardent Zionist.

Chesterton was convinced that without a homeland, the Jewish people lacked a native place to protect and develop, a place to serve as a refuge from attack. He predicted Jews would thus become vulnerable nomads who were never truly at home in any country, always seen as suspicious outsiders, putting them at risk for violent persecution—which is exactly what happened in the 1940s, after Chesterton’s death. In truth, Chesterton’s concerns were meant to help the Jewish people, not denigrate them. Like a prophet, he raised the alarm as their friend and defender, not as their enemy.

“It happened that when I was in America, I had just published some studies on Palestine and I was besieged by Rabbis lamenting my prejudice. I pointed out that they would have got hold of the wrong word even if they had not got hold of the wrong man. As a point of personal autobiography, I do not happen to be a man who dislikes Jews, though I believe that some men do. I have had Jews,” this is by the way very true, throughout his life, “I have had Jews among my most intimate and faithful friends since my boyhood and I hope to have them till I die. But even if I did have a dislike of Jews, it would be illogical to call that dislike a prejudice. Prejudice is a very lucid Latin word meaning the bias which a man has before he considers a case. I might be said to be prejudiced against a Hairy Ainu because of his name.”

Chesterton is lamenting the fact that he is being misunderstood. It is the lot of every person who writes for the public to, at some point, be misunderstood.

And he goes on, but he says, “But if after moving about in the modern world and meeting Jews, knowing Jews, doing business with Jews and reading and hearing about Jews, I came to the conclusion that I did not like Jews, my conclusion would certainly not be a prejudice, it would simply be an opinion and I should be perfectly entitled to hold, though as a matter of fact I do not hold it. No extravagance of hatred merely following on experience of Jews can properly be called a prejudice.”

Importantly, in this passage Chesterton twice confirms, “I do not happen to be a man who dislikes Jews.” He couldn’t be clearer. Those who think he does dislike Jews or agrees with Ford’s antisemitism must consider Chesterton a liar, if nothing else.

However, the point he makes here about prejudice is important. Chesterton was sometimes accused of being antisemitic simply because he disagreed with or disliked particular Jewish men he had encountered. This was sometimes confused for prejudice, or even antisemitism.

Yet disliking particular men who happen to be Jewish (or Irish, or German, or Russian) does not make someone racist. Chesterton himself reminds us what prejudice is: it is judging a person based on a characteristic of theirs before meeting them. This is what racists do; they prejudge someone based on their ethnicity. However, as Chesterton explains, if one dislikes a person after meeting them, because of some experience, it is no longer defined as prejudice—it is an opinion.

To see this more clearly, swap out Jews for another people group, such as building contractors. Imagine a friend telling you, “I’ve met contractors, known contractors, and done business with several contractors, and after so many awful experiences, I’ve come to the conclusion that I just don’t like contractors.” Few of us would be surprised or offended by that conclusion. In fact, many of us have voiced that very opinion ourselves!

That conclusion doesn’t mean we’re prejudiced against contractors or have a bias against them, nor does it mean there aren’t individual contractors that are actually pleasant and fair. It just means that, in our experience, the contractors we’ve dealt with have been generally disreputable, and as a consequence we dislike them. That’s not a prejudice—that’s an opinion, based on experience. And it’s the distinction Chesterton is trying to make here.

There’s just something off here that we can’t deny it as Chesterton, but it’s not the Chesterton that we admire who shaped us, who made us want to be better human beings, better Christians, better Catholics.

This may be Goldstein’s opinion, but we disagree. There’s only one Chesterton.

So he goes on and he says, you can read these, “People of the plains have found the Jewish problem exactly as they might have struck oil because it is there and not because they were looking for it.”

See the above note about “the Jewish problem” and what it actually means.

Going to skip ahead. And he says, “It has appeared because it is a problem and those are the best friends of the Jews, including many of the Jews themselves, who are trying to find a solution. That is the meaning of the incident of Mr. Henry Ford of Detroit, and you will hardly hear an intelligible word about it in England.”

Now I don’t know what Chesterton means by that last sentence, I’m not a historian, which is why so much of this was new to me. But I have to say when I read him saying, “You will hardly hear an intelligible word about it in England,” that implies that in England, there was an uproar about Henry Ford’s prejudice.

We appreciate Goldstein admitting she’s not a historian and that these passages are new to her, despite them being familiar to millions of Chesterton readers, as they’re found in one of Chesterton’s most famous books, What’s Wrong with the World. But in that case, we wonder, why is Goldstein lecturing others about what they might mean?

Again, Goldstein seems to draw precisely the opposite conclusion from what Chesterton actually meant. To understand that last line—“you will hardly hear an intelligible word about it in England”—you have to look two paragraphs back in the chapter, where Chesterton explains clearly what he’s referring to. There he says:

“He [Henry Ford] is chiefly known in England for a project which I think very preposterous; that of the Peace Ship, which came to Europe during the war. But he is not known in England at all in connection with a much more important campaign, which he has conducted much more recently and with much more success; a campaign against the Jews like one of the Anti-Semitic campaigns of the Continent.”

Chesterton is acknowledging two things here. First, that Henry Ford is “against the Jews” and has launched an antisemitic campaign, and second, that very few people in England are aware of this fact. Chesterton is not saying what Goldstein claims, that in England “there was an uproar about Henry Ford’s prejudice.” He’s saying exactly the opposite, that the English have ignored Ford’s campaign against the Jews. This is yet another example of Goldstein’s confusion about Chesterton’s writing.

It’s important to add that Chesterton, multiple times, makes clear that he disagrees with Ford’s antisemitism. In this same section as the line above, he says Ford “is a man quite capable of views which I think silly to the point of insanity,” presumably referring to Ford’s antisemitism (though also his pacifism), and that a man such as Ford “is always capable of being wildly wrong . . . and Mr. Ford has been wrong before and may be wrong now.” Chesterton was surprised to find that Ford had a dislike of a particular group of people, because the reputation—and creed—of America was that “all men are created equal.”

Goldstein seems to think that Chesterton agrees with Ford’s opinion of the Jews, even though Chesterton states that he does not. He is saying here, in essence, “There are people who dislike the Jews. I don’t, but Ford does.” And Chesterton is surprised to discover this given that Ford is both an ardent pacifist and an American.

Chesterton on Hitler

So, now, one might think that when Adolf Hitler came to power and began to send out his brown shirts to engage in organized attacks upon Jews, Chesterton would soften his stance towards the Jewish people. In fact, his writings about Jews from that time onward grow more flippant.

This is not true, as we’ll come to see. However, before examining the quotes put forth by Goldstein, it’s important to understand this timeline:

- 1874 – G.K. Chesterton is born

- 1914 – World War I begins

- 1918 – World War I ends

- 1922 – G.K. Chesterton converts to Catholicism

- This same year, he also publishes Eugenics and Other Evils, a prophetic book warning of the Nazi program of Eugenics. He wrote this a year before Hitler wrote Mein Kampf and long before the concentration camps.

- 1933 – Hitler opens first concentration camp (Dachau) primarily to hold German political prisoners

- 1936 – G.K. Chesterton dies

- 1938 – Jews are first rounded up and deported to concentration camps

- 1939 – Hitler invades Poland, beginning World War II

- 1941 – The Holocaust begins, initiating the murder of six millions Jews

Every single person today knows about the Holocaust. However, Chesterton didn’t know. He lived prior to World War II, and he was unaware of the atrocities that were yet to take place against the Jews. He had hints, and he criticized them, but he of course couldn’t have fully known what Hitler would do. Therefore, we shouldn’t view Chesterton’s writings through a post-Holocaust lens. (If Chesterton had lived through the Holocaust, we can be sure he would be among the strongest and most vocal opponents of the Nazi persecution.)

Also, keep in mind that in the 1920s and 30s there were no televisions, no internet, and only a scarcity of international news. News from Germany was often propaganda, and the early attacks on Jews were often underreported or untold.

Finally, perhaps that which is interpreted by Goldstein as “flippancy” is satire. As Chesterton puts it, he and fellow Cockney humorists used satire because they “saw something delicate which they could only express by something indelicate.” If someone doesn’t understand Chesterton’s use of satire, it’s easy to see how it might be misinterpreted as flippant.

In late July 1933 he wrote in G.K.’s Weekly a quote, in “The Judaism of Hitler”, in which he claimed that Hitler’s idea of the master race had its origin in Jewry. In it, as this slide shows, I realize the writing’s quite small, he said of the Jews that quote, “They have been too powerful in Germany.”

With this line, Chesterton was raising an alarm, not about the Jews but for the sake of the Jews. He worried that if the Jews became too powerful in Germany, their prominence would breed resentment among Germans who would grow to hate the Jews, seeing them as usurping outsiders. And as a result, the Jews would be vulnerable to German persecution (a prophecy that was shortly fulfilled.) This was all part of what Chesterton and many others called the “Jewish problem” or the “Jewish question”: how can a people without a country successfully flourish within other nations without being seen as enemies or threats?

Of course, it’s difficult to hear this question raised in a post-Holocaust world, reading into it what we now know. We must keep in mind, however, that the Holocaust had not yet happened, and Chesterton did not have the ear of Adolf Hitler—he had the ear of England.

We certainly can assume, based on Chesterton’s life, that if he felt the Jews were too powerful in Germany, his solution would never have been to kill them. He instead wanted to help them.

Two months later Chesterton did give an interview to the London Jewish Chronicle in which he harshly criticized Hitler’s actions against Jews.

We appreciate Goldstein acknowledging this, as it seems to contradict her earlier claim that “his writings about Jews . . . grew more flippant.” It’s worth quoting this passage in full. In September 1933, six years before the start of World War II, Chesterton was interviewed by the Jewish Chronicle and said:

“I am appalled by the Hitlerite atrocities. They have absolutely no reason or logic behind them. It is quite obviously the expedient of a man who has been driven to seeking a scapegoat, and has found with relief the most famous scapegoat in European history, the Jewish people. I am quite ready to believe that [Hilaire] Belloc and I will die defending the last Jew in Europe.”

It’s worth considering both what he said and how it was reported at the time for the reporting gives some important historical context on how Chesterton was viewed in comparison with his contemporaries. So this is from an American newspaper that’s reprinting, it’s the B’Nai Birth Messenger, so an American Jewish newspaper that’s reprinting Chesterton’s interview with the Jewish Chronicle. And it says, I won’t read you the whole thing, but it says, “Hilaire Belloc and Gilbert K. Chesterton have been rated as being among the outstanding anti-Semites in the world. But today, these two celebrated men of letters are among the authors of the strongest denunciations of Hitlerism and the Nazi anti-Jewish barbarities.”

Again, this is the opposite of “his writings about Jews . . . grew more flippant.” Here we have an American Jewish newspaper acknowledging that Chesterton has offered some of the “strongest denunciations of Hitlerism and the Nazi anti-Jewish barbarities.” The newspaper adds that Chesterton “has handed down a verdict on Naziism which should cause Hitlerites everywhere to sit up and take notice.”

And he [the newspaper editor] goes on and then he quotes Chesterton, “We quote Mr. Chesterton’s statement: ‘In our early days, Hilaire Belloc and myself were accused of being anti-Semites. Today, although I still think there is a Jewish problem, and that what I understand by the expression the Jewish spirit is a spirit foreign in western countries, I am appalled by the Hitlerite atrocities in Germany.’” And he goes on and he says that Hitler has been driving to seek a scapegoat and has found with relief the most famous scapegoat in European history: the Jewish people. And then Chesterton finally says, “I am quite ready to believe now that Belloc and myself will die defending the last Jew in Europe. Thus does history play its ironical jokes upon us.”

I would just say that if you’re going to speak against Hitler’s treatment of the Jews in 1933, it would be good to not say, by the way, there really is a Jewish problem.

It’s easy to mistake discussion about the “Jewish problem” as antisemitism, as Goldstein seems to imply.

Yet once again, it’s important to understand what Chesterton means when he uses this phrase. Goldstein uses the phrase “Jewish problem” five times during her talk without ever once defining it—a major shortcoming. This leaves the impression on listeners unfamiliar with this phrase that Chesterton might be describing Jews themselves as a problem.

However, as we noted above:

When writing about “the Jewish Problem”—better called “the Jewish question”—Chesterton wasn’t implying that the Jews were a problem, as Hitler believed, but that they had a problem, namely that they were a nation without a country. They lacked a homeland. And Chesterton wanted to help them solve that problem, which is why, with support from Jewish friends, he became an ardent Zionist.

Chesterton was convinced that without a homeland, the Jewish people lacked a native place to protect and develop, a place to serve as a refuge from attack. He predicted Jews would thus become vulnerable nomads who were never truly at home in any country, always seen as suspicious outsiders, putting them at risk for violent persecution—which is exactly what happened in the 1940s, after Chesterton’s death. In truth, Chesterton’s concerns were meant to help the Jewish people, not denigrate them. Like a prophet, he raised the alarm as their friend and defender, not as their enemy.

Goldstein thinks Chesterton’s strong denunciations against Hitler and his commitment to defending the Jews are at odds with his writing about the “Jewish problem.” But the opposite is true. Once we understand what Chesterton means by this phrase, we see how it perfectly harmonizes with his assertion that he and Belloc “will die defending the last Jew in Europe.” In both cases, Chesterton was expressing his support for the Jews, concerned as he was for their health and happiness.

And even he admits it’s an irony isn’t it, there’s a flippancy about this.

The reason why Chesterton describes this as an ironic is because some people accused Chesterton of being antisemitic, as Goldstein seems to do, and yet this supposedly antisemitic man was hailed by Jewish newspapers for offering some of the “strongest denunciations of Hitlerism and the Nazi anti-Jewish barbarities” and agreed to go to his death defending the Jews. That’s not flippancy; that’s irony.

Chesterton on the Nazis

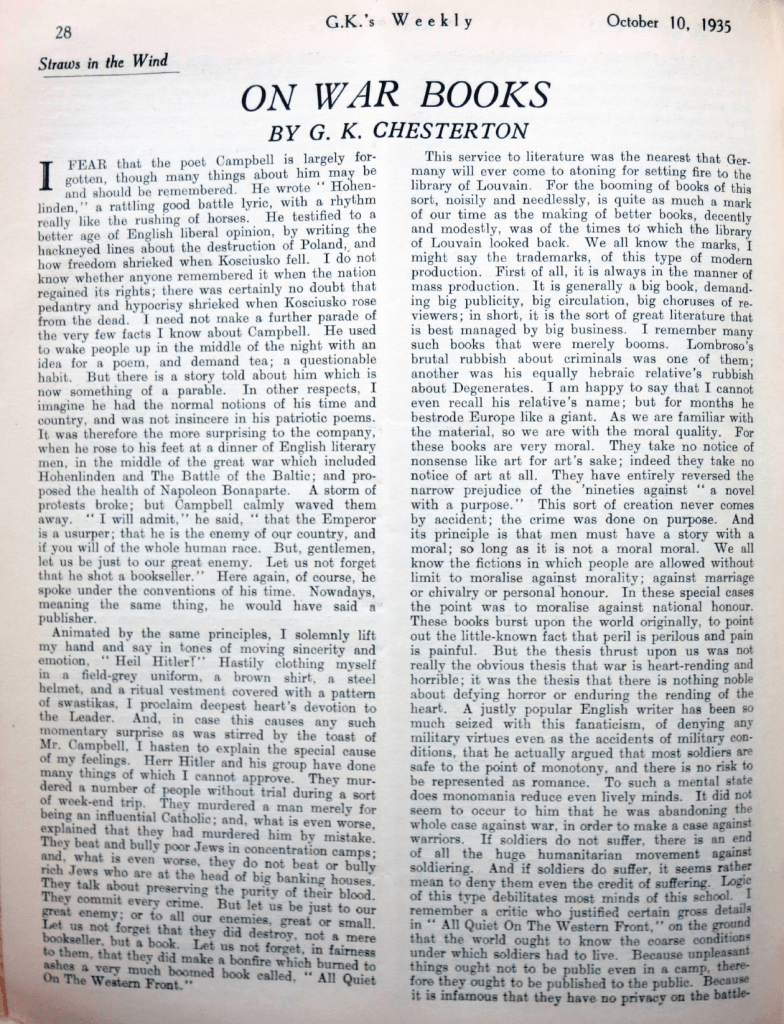

So, my final example is the essay that I mentioned to you before, it’s also one of Chesterton’s final public writings on Jews. He published this essay “On War Books” in G.K.’s Weekly, October 10th, 1935, eight months before his death. This is the one that I ordered from the library so that I could see the exact words because reading it in Simon Mayers’ [blog] and reading him say that there was something that was deleted, I thought, if I’m going to get up before the Chesterton Conference and say that G.K. Chesterton said this, I’d better have proof—I better have the actual print.

So, this is “On War Books,” and here’s the quote. Chesterton says, “Herr Hitler and his group have done many things of which I cannot approve. They murdered a number of people without trial during a sort of weekend trip.” This is a flippant way, by the way, of speaking of the Night of the Long Knives . . .

This article was published on October 10, 1935. The Night of the Long Knives occurred from June 30 to July 2, 1934, a Saturday, Sunday and Monday. The people killed that weekend were all Germans, many military leaders, most opposed to Hilter in the past or present, whom Hitler wanted to eliminate, and show his power. Around 700 to 1,000 people were killed that weekend with no trial. Chesterton’s way of describing it as a “sort of weekend trip” is his usual way of speaking lightly about a very distressing subject.

But this isn’t flippancy. As we quoted before, Chesterton says that he and fellow humorists used satire because they “saw something delicate which they could only express by something indelicate.”

. . . and he goes on to say. “They murdered a man merely for being an influential Catholic, and what is even worse, explained that they had murdered him by mistake.” Some of you may know the name of that person, I can’t think of it offhand, but it was a very holy Catholic who resisted Hitler.

Then he says, and this is what you have read, this first part, “They beat and bully poor Jews in concentration camps.” Now in the Frank Sheed version [of this essay] which is also reprinted in Michael Coren in defending Chesterton against antisemitism, Michael Corren says, full stop, look, Chesterton put down the Nazis for beating and bullying poor Jews in concentration camps.

Frank Sheed, although he did many, many good things in his life, he did not do us a favor by excising the last part of that so that we could know the truth of what Chesterton wrote and know it first ourselves without being told it by people who are outside the Chesterton community.

Chesterton goes on to say, “And what is even worse, they do not beat or bully rich Jews, who are at the head of big banking houses.”

Some background may be helpful here to understand what Goldstein is referring to. In 2013, the blogger and online Chesterton critic Simon Mayers noted that in a 1935 essay entitled “On War Books”, Chesterton condemned “Herr Hitler and his group” for “beat[ing] and bully[ing] poor Jews in concentration camps.” Chesterton added, “What is even worse, they [the Nazis] do not beat or bully rich Jews who are at the head of big banking houses.”

Chesterton wrote this essay in 1935, and then five years later it was published in a posthumous essay collection titled The End of the Armistice, a book edited by Frank Sheed. However, the book version of the essay omitted the sentence lamenting that rich banking Jews had escaped beating and bullying. Presumably the decision to remove that sentence was made by Sheed, the book’s editor and publisher.

Now, before drawing any conclusions about these claims, we need to answer two questions. First, what did Chesterton mean when he wrote that sentence? And second, why did Sheed remove it?

First, what did Chesterton mean when he wrote this sentence? Within the context of the article, and taking into consideration Chesterton’s typical sarcasm and wit, the sentence is not about antisemitism at all. Chesterton wasn’t celebrating Jews being dragged into concentration camps, which he deplored repeatedly throughout the 1930s. He was condemning the fact that Jewish bankers were conspiring with Nazis and getting rich from the Nazi regime, even as their fellow Jews were being persecuted by those same Nazis. Chesterton was condemning the hypocrisy of the Nazis and the betrayal of Jewish bankers.

(And Chesterton wasn’t alone in this view. Even Jewish leaders, such as Dr. Max Nordau, whom Chesterton called “the most brilliant Jew of this age,” criticized Jewish millionaires, saying, “These money-pots who despise what we honour and honour what we despise . . . Many of them forsake Judaism and we wish them God-speed, only regretting that they are at all of Jewish blood, though but of the dregs.”)

If you’re unfamiliar with Chesterton’s satirical style, and if you strip this one line out of context and interpret it in the worst possible way, you might arrive at the faulty conclusion Goldstein did, that Chesterton here is suggesting rich Jewish bankers be sent to concentration camps. But that clearly wasn’t his point. His point was that Jewish bankers should not conspire with Nazis, getting rich by betraying their own people. In truth, the sentence is not antisemitic in any way—just the opposite. Chesterton is condemning the Nazis and those who conspire with them to persecute poor Jews.

But then the second question: why did Frank Sheed decide to remove this sentence? Unless we find definitive evidence, the honest answer is, “We don’t know.” We can only guess at Sheed’s motives. Of course, Goldstein shows no such humility and simply assumes, without evidence, that Sheed deemed the sentence “too antisemitic” and therefore removed it in order to soften Chesterton’s image and “supress” his antisemitism.

However, Frank Sheed was an experienced editor and publisher. He knew, as all good editors know, that sometimes passages are removed not because they are bad in themselves, but because they might be confusing and open to misinterpretation. Sometimes it’s better to drop a potentially distracting line, especially if it doesn’t contribute much to the overarching point of the essay or book.

That seems to be the case here. It’s likely Sheed was aware that some readers, a small minority, might have missed Chesterton’s sarcastic point and misinterpreted the line as promoting antisemitism, and Sheed thought it better to just remove the line to avoid that confusion—not because the line was antisemitic, but because some people might mistakenly read it that way. Again, this is what good editors do, and Sheed was a good editor.

So, in conclusion, what did Chesterton actually mean here? Again, in this sentence he was decrying the fact that rich Jews were in collusion with Nazi Germany. He was not suggesting that rich Jews should literally be sent to concentration camps. His point was that the rich Jews were treated differently by the Nazis. The Nazis were hypocrites for beating people for being Jewish but only if they were poor, not rich, and only if they were of no use to the Nazis. Chesterton was pointing out yet another layer of evil in the Hitler/Nazi regime.

This, I might add, is two years after he gave his interview saying that he’ll go down defending the last Jew in Europe. My head exploded when I read this.

We understand this kind of knee jerk reaction, and sympathize with it. However, as Chestertonians, we’re committed to understanding what Chesterton was trying to say before passing judgment on it. We understand that an initial surface reading of any sentence may seem awful and perhaps flippant. But we must try to understand what Chesterton was saying from his point of view, in his style, in his point in time.

And then he goes on, “They [the Nazis] talk about preserving the purity of their blood. They commit every crime. But let us be just to our great enemy; or to all our enemies, great or small. Let us not forget that they did destroy, not a mere bookseller, but a book. Let us not forget, in fairness to them, that they did make a bonfire which burned to ashes a very much boomed book called [All] Quiet on the Western Front.”

So, Chesterton, being flippant in 1935, says, “Hey, we can say one good thing about the Nazis? At least they burned All Quiet on the Western Front.” What to say? I need time to process this. I don’t know about you, I need time. But I think we better process this now and we better get in front of this story before the whole world gets this story, and we have to process it honestly.

In this passage, Chesterton is clearly mocking the Nazis. He’s saying that their only positive quality is that they burned a popular but subpar novel. And that’s it—the Nazis have no other praiseworthy traits. Chesterton is using satire to mock them.

(Chesterton didn’t like the book because he thought it too pacifist and obscene.)

The drama of Goldstein’s reaction is therefore greatly exaggerated. It should not be “mind blowing” to encounter Chesterton mocking the Nazis. And if Goldstein has not had time to “process” this information, it seems premature to give a speech about it.

Her urgency to “get in front of the story” also makes little sense. There is no story here. Chesterton’s words do not need any defense, particularly on this point. He is making a joke that burning a book he dislikes is the only laudable action of a terrible tyrant.

Chesterton’s Legacy

And I think that helping us process it we can honestly look at the good that Chesterton did which is in those, among other things, many other things, those moral imperatives that I discussed, and we should ask, did Chesterton, in writing about Jews, place language at the service of truth? Did he place his personal judgment at the service of truth? Did he call out sin for what it is? Did he employ reason and not fads or fancies? Did he follow permanent standards of morality? And did he resist evil within himself and within society?

And if he didn’t, we need to say that he didn’t, we need to say that this was a terrible blind spot, we need to even say that we’re going to do penance for this.

The work of “processing” perceived wrongs is best done with a spiritual director, therapist, or within a scholarly community, not from the podium at a large conference, nor on Twitter. If Goldstein feels some shock or discomfort at Chesterton’s words, it may be fruitful to try to analyze those feelings with a trusted friend or guide. But since her experience of the text is clearly not universal, it is not required that all people who love Chesterton need to do the same processing work that Goldstein seems to require.

Goldstein’s assessment is clear: she believes Chesterton had a blind spot and was guilty of serious sin. She believes he was antisemitic. She has offered a few passages to make her case, but as we’ve seen, she has not interpreted those passages correctly. She has ignored their context, both historical and literary, and in some cases arrived at the exact opposite conclusion from what Chesterton intended to convey. She has not carefully studied Chesterton’s works with trusted scholars, relying almost exclusively on the analysis of a self-published blogger. And she seems unable to grasp Chesterton’s satirical style.

Nevertheless, Goldstein is entitled to her own conclusions. We respect that. And if she detects shortcomings in Chesterton and feels strongly about doing penance for them, we admire her willingness to right these perceived wrongs in the spiritual order.

However, if Goldstein suggests that the entire Chesterton community as a whole is wrong about Chesterton, has overlooked grave sins, and has suppressed and covered up any antisemitism, then she is indeed wrong.

But we need to say all the more that, as with Richard Wagner, there is something great in Chesterton that should not die, that is for the ages. And this brings me to my closing. I’d like to share with you a question I was asked by my Pius XII historian friend William Doino, Jr. William, in addition to being a Pius XII historian, is also an editorial collaborator of Alice von Hildebrand. He wrote the historical footnotes for Dietrich von Hildebrand’s memoir, My Battle Against Hitler.

And so, as William and I were discussing the things that I had read in Simon Mayers’ book, he asked me whether I believed the Chesterton community should continue to have Chesterton canonized a saint. And I said to him what I will now say to you: I believe we should speak about how many saints read Chesterton. We should tell the world that reading Chesterton helps make saints. We have the power to convince the world that Chesterton’s writings help make people holy.

Amen! We wholeheartedly agree! Chesterton changes lives. He helps make saints. This is the greatest testimony to his goodness and among the strongest arguments for his sanctity.

And the way we do that is by showing that we ourselves have become more holy through reading Chesterton the way he would want us to read him, taking what is good and leaving behind those things that are not edifying. Thank you, God love you. [End of talk]

Notice the shift in language in this final sentence of Goldstein’s talk. It’s quite the turnaround. For most of her talk, Goldstein attempted to show that Chesterton was guilty of grave sin, the sin of racism, particularly antisemitism. She suggested that as a result of these serious failings we should denounce some of Chesterton’s writings and do penance for his sins, necessary steps if his legacy is to endure.

By the end of her talk, however, she simply suggests we should “leave behind those things [in Chesterton’s writings] that are not edifying.”

There’s a chasm of difference between these two proposals. Accusing someone of grave sin is far different than simply skipping parts of an author’s work that you don’t find helpful. The first approach is controversial and, we believe, completely unjustified in Chesterton’s case. The latter is a basic principle that holds for any reader studying any author.

Q&A Period

[Note: After Goldstein’s talk there was a brief question and answer period.]

If there are any questions, I’m happy to answer them.

QUESTION: Is any criticism of the Jewish people anti-Semitism? Is any criticism of Christians by Jews anti-Christianity?

GOLDSTEIN: That’s a very good question. Is any criticism of Jews anti-Semitism? Is any criticism of Christians by Jews anti-Christianity? Well, one thing that Chesterton said, that Simon Mayers agrees on—there’s not a lot that they agree about—but one thing they agree on is that the word anti-Semitism is just a terrible word because nobody hates Semites. Semites are Semitic peoples that are not only Jews but also people from Lebanon, Catholics, Muslims, people from elsewhere in the I think the Levant. So the word anti-Semitism is misleading.

And I suppose the best answer to say is that, it’s always good to make distinctions. It’s always good if we are criticizing people who happen to be Jewish, or organizations that happen to be Jewish, to criticize them for what they’re doing that is worthy of criticism and to criticize them as specifically as possible. So, if a Jewish person is doing bad—doing something bad—say, “This person is doing something bad” and not say that, “Well, they’re part of all these Jews who are doing those things.”

It seems to us as if this is exactly the approach we Chestertonians are taking, and the exact approach Chesterton himself took, which Goldstein seemed so critical of earlier in her talk.

And likewise with with Christians. I mean, I think myself of the anti-Catholicism that we see where in certain states there have been, I think Delaware is one of them actually, if I’m not mistaken, or certainly Connecticut it might be, there have been efforts with sex abuse cases to have the statute of limitations extended for reporting sex abuse crimes, so that it targets Catholics—just the statute of limitations extended for the Catholic Church, but not for anyone else. And that is anti-Catholicism, that is an anti-Christianity. We should speak up about not necessarily that we should oppose extending the statute of limitations, but we should oppose being targeted because of our faith. And so there’s nothing prejudicial or wrong about saying we want to be able to prosecute abusers, but if you’re wanting to prosecute abusers, speak about prosecuting abusers no matter whether they’re Catholic or not, not just Catholic ones.

So, that would be my answer to try to make our language as specific as possible to people or to social or civic organizations or governmental organizations that are doing things but not to use the faith or ethnic group as a blanket descriptor, thank you.

QUESTION: Hi. First, thank you for your research, I enjoy your study. But my question is, do you think the framing of anti-Semitism, especially against the Nazis, could almost get more muddled in with the wider context looking back? I remember when I read about G.K. Chesterton, he supported Dr. [Engelbert] Dollfuss of Austria who also despised the Nazis but was himself a fascist dictator aligned to Mussolini and Hungary. So, do you think that maybe, you know, trying to defend the context of this very different time of post-war Europe that was filled with well, post-war Europe, we all know what that is—do you think that maybe trying to always defend these criticisms almost can’t get anywhere, or do you think you can actually solve them because one criticism, one justification of Chesterton might lead to another criticism? Like you are against the Nazis, but you defended Mussolini and Dollfuss, who were also fascist dictators who maybe weren’t anti-Semitic, but had their own concentration camps.

GOLDSTEIN: I think that’s a very good point. I think that we have to be careful not to over-contextualize because that will get us into trouble. . .

On the contrary, it seems that in these critical passages, context is everything. It is taking Chesterton out of context that gets us in trouble.

I was reading a very good review by Christendom professor Adam Schwartz of the Ann Farmer book . . .

It remains unclear whether Goldstein has actually read this book by Ann Farmer, titled Chesterton and the Jews, which is by far the most comprehensive and well-balanced study to date. It offers a careful and detailed look at the question, examining all the evidence and, most importantly, placing it in context.

. . . and he pointed out that, this is the Ann Farmer book on Chesterton and the Jews, and Ann Farmer doesn’t refer to Simon Mayers’ research except in a footnote. She ignores many of the things that he brings out and she in many places minimizes and tries to I would say over contextualize things that Chesterton said. And one of the arguments she makes is that Chesterton was a man of his time and in his time people were saying that.

The problem is, as soon as you say that, you run into two things. Number one, you run into Chesterton’s own words which are that moral standards are unchanging, so what’s right in one age is right in another, what’s wrong in one age is wrong in another.

This has been addressed above in response to Goldsteins fifth Chesterton imperative, “I must recognize and follow permanent standards of morality.”

Number two, how do you reconcile Chesterton’s behavior with how Tolkien wrote about Jews, where he was willing to not have Lord of the Rings published in Nazi Germany rather than have to tell the Nazis that he was Aryan? Because they wrote asking, are you Aryan, and he and he wrote back this letter basically making fun of them, first pointing out that Aryan isn’t a real ethnic descriptor, not the way they think it is, and second, saying I am sorry that I am not gifted with Jewish blood or something like that.

Goldstein is a little mixed up about this incident. After Tolkien published The Hobbit (not Lord of the Rings) in 1937, he received a letter from a Berlin publisher in 1938, expressing interest in publishing a German edition of The Hobbit. But they first wanted proof that Tolkien was of Aryan descent. You can read Tolkien’s wonderful reply here. He says, “If I am to understand that you are enquiring whether I am of Jewish origin, I can only reply that I regret that I appear to have no ancestors of that gifted people.” (Chesterton also described the Jews as “a gifted people.”)

Three years later, in 1941, Tolkien wrote a letter to his son Michael which said:

“I have in this war a burning private grudge against that ruddy little ignoramus Adolf Hitler. Ruining, perverting, misapplying, and making for ever accursed, that noble northern spirit, a supreme contribution to Europe, which I have ever loved, and tried to present in its true light.

Again, it’s important to remember that G.K. Chesterton died in 1936. He didn’t live as long as Tolkien, who died in 1973, to see the full evils of Hitler and Nazism. Thus it’s unfair to criticize Chesterton for not responding to the Nazis in the mid-1930s as Tolkien did in 1941.

Of course, Chesterton did harshly criticize the Nazis. A search of Chesterton’s writings between 1933 and 1936, the last three years of his life, finds him speaking out against Hitler and Hitlerism over 150 times.

In April 1933, Chesterton referred to “the madness of Mr. Hitler.” Then in September 1933, six years before the start of World War II, Chesterton said in an interview with the Jewish Chronicle: