I was recently reminded of an old joke about education. According to the joke, there are three great reasons to be a teacher: June, July, and August. Now, I haven’t heard this joke among Chesterton Academy faculty members, but I have heard teachers in other settings make further statements that imply that they actually may have a distaste for teaching. In my days as a university professor, I once heard another employee of the college say, “This would be such a lovely institution, if it weren’t for the students.” And finally, let me ask, have you ever spoken with a public-school teacher who notes their “number of years left until retirement,” immediately after you are introduced to them?

The general attitude that these jokes and statements express brings me to ask a question: “How can teachers expect their students to love learning, if the teachers themselves fail to value the material and the lessons they are teaching?”

While I am always careful to avoid an allegiance to methodology as an end itself, it is important to note that the Classical approach is an antidote to this trend because the core of Classical education is the cultivation of a sense of wonder that fosters a love of learning and a desire for wisdom and truth.

In Plato’s Socratic dialogue with Thaeatetus, Socrates says, “Wonder is the feeling of the philosopher, and philosophy begins in wonder.” This is also the dialogue in which Plato provides insight into his approach to applying our innate sense of wonder to the acquisition of knowledge. In the dialogue, Socrates is seeking to answer the question, “What is knowledge,” and eventually Thaeatetus says:

I can assure you, Socrates, that I have tried very often [to answer], when the report of questions asked by you was brought to me; but I can neither persuade myself that I have a satisfactory answer to give, nor hear of any one who answers as you would have him; and I cannot shake off a feeling of anxiety.

Socrates replies, “These are the pangs of labour, my dear Theaetetus; you have something within you which you are bringing to the birth.”

Socrates then makes an extended analogy of his technique of seeking answers to the techniques of ancient Greek midwives, who would assist women in the birth process, though they themselves were typically elderly or barren. Socrates says:

… my art of midwifery is in most respects like theirs; but differs, in that I attend men and not women; and look after their souls when they are in labour, and not after their bodies: and the triumph of my art is in thoroughly examining whether the thought which the mind of the young man brings forth is a false idol or a noble and true birth. And like the midwives, I am barren, and the reproach which is often made against me, that I ask questions of others and have not the wit to answer them myself, is very just …

One concludes that Plato, through the voice of Socrates, sees the teacher not as a master who imparts his knowledge, but one who facilitates the “moment of birth,” the moment of discovery. He saw the student as equally important in the discovery and believed that the student and teacher were both part of something greater.

I often tell my students at Chesterton Academy of the Sacred Heart that they are the class. They must prepare ahead to contribute to the discussion, and they are not allowed to simply take my ideas and knowledge out of my head. Every individual is valuable when we approach this discussion with wonder.

The approach calls to my mind the Oxford scholar in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, one of the few characters to whom Chaucer is charitable in his prologue: “… Filled with moral virtue was his speech / And gladly would he learn and gladly teach.” The Socratic seminar emphasizes that we are all students, and we are all teachers.

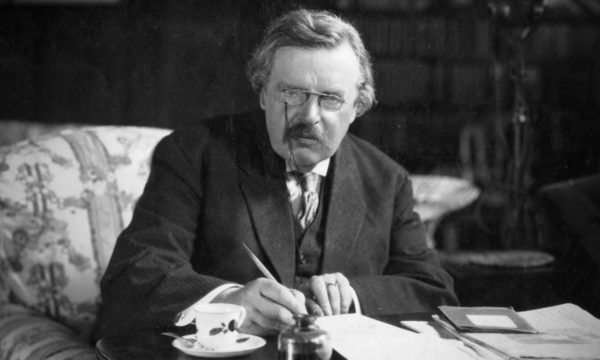

I want point out how very “Chestertonian” the Classical method is. Who is better at renewing a sense of wonder at the most familiar things than G.K. Chesterton? This is why Chesterton’s writing are changing lives; they have changed my life, and they are inspiring our students to passionately pursue Christ.

For example, in the chapter of The Everlasting Man titled, “The Riddles of the Gospel,” Chesterton suggests that we should be shocked by the words and actions of Christ, if we can imagine that we are reading them for the first time.

Second, Chesterton is the king of the “paradox,” which I have often mused is only a word that we, as finite humans, have invented to marvel at “business as usual” for a God who does the impossible.

Finally, there is the great passage in “The Ethics of Elfland” where Chesterton suggests that the sun may rise in response to God saying “Do it again,” each day. One of our Chesterton Academy students responded to this passage in her senior capstone essay by saying, “This claim is supported by the fact that the sun refused to shine on the day men killed God.”

This student’s reflection is a powerful example of the renewed sense of awe at our faith that is the result of a Chesterton Academy education. Through the application of Classical methods, the study of the truths contained in the Catholic Church, and the exploration of the wit and wisdom of G.K. Chesterton, the schools are raising up a generation of joyful disciples of Christ who are filled with wonder and gratitude. Whatever the state of education elsewhere, these students are finding profound meaning in their very existence and joyfully bringing others to the Church.

ABOUT JOSHUA RUSSELL

Dr. Joshua Russell is Headmaster at Chesterton Academy of the Sacred Heart in Peoria, Illinois, and is an Academic Dean of the Chesterton Schools Network. This essay is based on a talk he gave at the Chesterton Schools Network Summit in June 2024.