We believe there really is a peril. It is not so much in the actions as in the assumptions. It is not so much in the sins for which individual sinners are pilloried, as in the sins for which they are not pilloried; the sins that seem to be no longer regarded as sins at all. It is in the things taken for granted; the things passed over; even the things forgotten, that the glaring change appears. It is involved in the very words used to whitewash it. People say, “There were blackguards like that a hundred years ago and in every age.” The answer is “Yes; there were blackguards like that a hundred years ago. But there were not respectable people like that a hundred years ago. Society did not assume a convention of sin, which only became unconventional when it actually turned into crime. It is not that more people have broken the law; it is that the law is broken; broken in the sense of having broken down.”

G.K.’s Weekly, April 4, 1925

Once again, one hundred years before the fact, G.K. Chesterton tells us what’s going on right now.

Sins are no longer regarded as sins. Sin is respectable. The law has broken down. And the peril is real.

The law is not just permitting sin. It is enforcing sin. Those who offer opposition to sin are now outlaws. Consider the sins our sorry society has come to accept as law. Easy Divorce. Entitled contraception. Perverse sex that is not merely sanctioned but enshrined under the sacred word “marriage.” And the latest and most absurd: the mutilation known as transgenderism. All of which would have been unimaginable a handful of decades ago. But Chesterton imagined it. He prophesied it.

In the end, he says, the exaggeration of sex becomes sexlessness. We are no longer drawn to the bait on the hook. We are drawn to the hook itself.

The only debate, as Chesterton predicted, is not about what is evil but what evils are excusable.

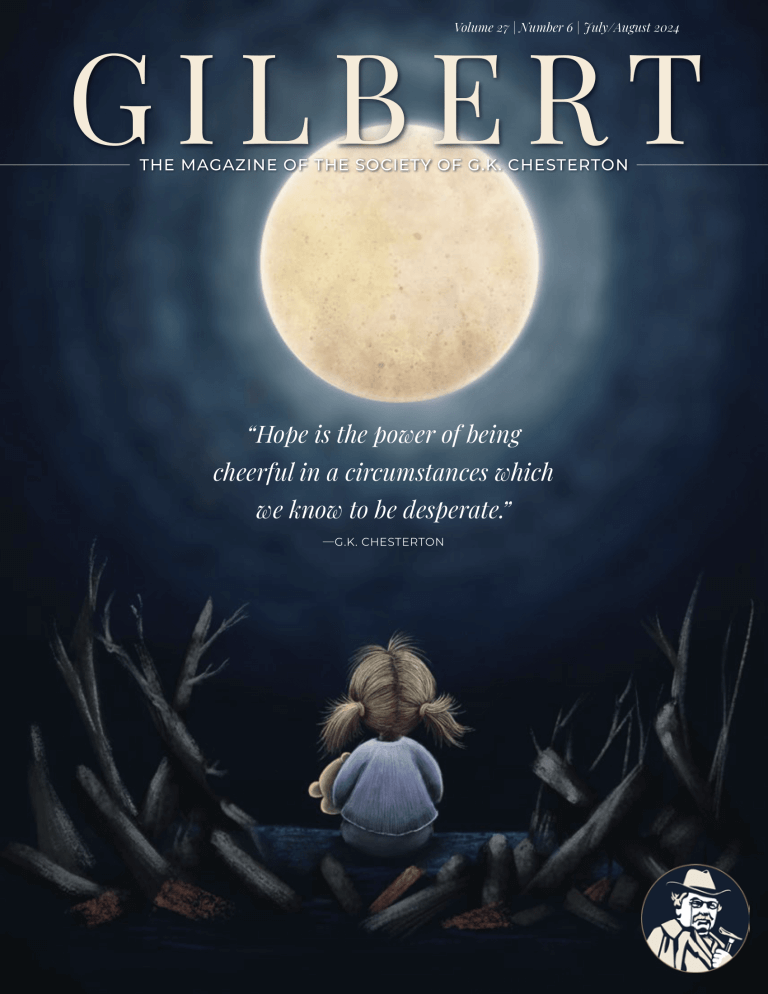

The peril is real. The pitfalls. The falling into the pit. The danger is nothing less than damnation. But what is also real, exceedingly real, is the way out of that path to peril.

We can still turn things around.

But will we? Are we? Think about this. Abortion has lost its status as a national right and has become a local battle again – which we are losing at an incredible rate. What are we going to do about that? We can start by making the issue even more local. Even more local. It starts in our homes, where we nurture life. Family life. From there we spread the culture of life to our neighborhoods, then to our communities, to our cities, to our states. The culture has to change in order for the laws to change. But it has to start at the local level. The followers must become leaders.

I suggest that our role is not that of street corner preachers screaming the warning that the end is near (though even these serve their purpose for the few souls who happen to be on the street and who somehow respond and repent). We have to make the case for truth without the focus on condemnation, that is, we must present the good as invitingly as possible, not merely as bait but as the feast itself. We have something very good to offer. An alternative to sin.

Sin is slavery. Even though slaves want to be free, they enjoy the security of slavery. Freedom means responsibility. The slave has lost his responsibility. Responsibility is harder work than being told what to do and what to think and what to expect. But at a certain point the slave who is shown no dignity and respect realizes that he must at least respect himself. It is then that he sees that he wants to be free. Even if freedom is the harder road.

I was drawn to Chesterton for many reasons. First of all, he delighted me. Even before I understood him. I knew this man was on my side. Or rather, I knew I was on his side. Or rather, I knew I wanted to be on his side. I was enchanted by his ability to state the truth so succinctly and potently and pleasingly plain. But I never thought in those early days that the pleasure of reading Chesterton would prove to be so important. To read Chesterton is to want to repeat him. To repeat what he says is not just a tonic for ourselves, it is a benediction for others. That is one of the reasons the Society of G.K. Chesterton exists. It is his good words that our families and friends, adversaries and enemies not just need to hear but – ultimately – what they want to hear. Wherever they have strayed, wherever they have fallen, wherever they are stuck, they know, yes they know, that they really do want to find the way out. Here is a prophet who points to that way by artfully telling them what they already know. “All men,” he says, “long to confess their crimes more than a thirsty beast longs for a drink of water.” There is the path to freedom.

ABOUT DALE AHLQUIST

Dale Ahlquist is President of The Society of Gilbert Keith Chesterton, a worldwide lay apostolate dedicated to Catholic education, evangelization, and the social teaching of the church. He leads the Society’s Chesterton Schools Network, which exists to inspire and support the creation of joyfully Catholic, classical, and affordable high schools around the world. Learn More