In my 26 years, I have an admission that might surprise fellow bibliophiles: I tend to not enjoy re-reading books. Although I occasionally notice new insights the second time around, the familiarity of the plot in fiction or the arguments in non-fiction generally dampens the experience for me. Perhaps my perspective will shift with time, but so far I can count on two hands the books I’ve voluntarily revisited outside of academic settings.

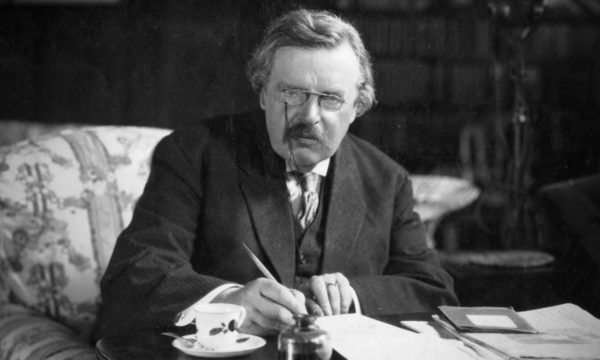

Lately, however, this aversion has started to wane as my life settles into a steadier rhythm. To my own surprise, I’ve been revisiting books that left a lasting impact on me. I recently re-read Chesterton’s Orthodoxy, a favorite of mine by my favorite author, alongside 1984 by George Orwell, among others. The experience left me struck by the unexpected similarities between Chesterton’s Orthodoxy and Orwell’s 1984.

Orwell’s dystopian world in 1984 vividly illustrates the horrors of a surveillance state where the government exists solely to perpetuate itself rather than to serve humanity. Chesterton, while never living to read this work of his fellow Englishman or to witness the rise of the socialist and communist regimes Orwell critiqued, anticipated a similar kind of dehumanizing governance. Chesterton championed principles that make us truly human – localism, love of fellow man and woman, tradition, the family – all of which are glaringly absent in Orwell’s world. And just as Chesterton’s reflections on society contain universal truths that resonate across ages, Orwell’s portrayal of an omnipotent state serves as an enduring caution against the psychological, philosophical, and humanitarian costs of unchecked power (that is, if his book itself survives the fate it warns against: the burning of books).

On this second read-through, I noticed a particularly striking similarity lying in Orwell’s use of the term “orthodoxy” and its opposite, “unorthodoxy.” In Orwell’s dystopia, to be orthodox means to align completely with the Party’s doctrine in thought and action. This rigid orthodoxy necessitates “doublethink” – a profound self-delusion that demands not only believing falsehoods but also forgetting the mental acrobatics used to arrive there. As one character chillingly observes, “Orthodoxy means not thinking – not needing to think. Orthodoxy is unconsciousness.” This version of orthodoxy ensures control over the individual, who becomes valuable only as a tool to maintain the Party’s power. Within this society of relentless surveillance, broken families, and ultimate distrust, even children are trained to report their parents for “thoughtcrime.”

In Orwell’s world, unorthodoxy, by contrast, is expressed as free thought and individuality. Unorthodox individuals retain their agency, common sense, and curiosity – qualities the Party ruthlessly suppresses by “vaporizing” any dissidents.

For Chesterton, however, orthodoxy stands for the freedom to think independently and explore beyond the mainstream narrative. To be orthodox in Chesterton’s sense is to escape intellectual stagnation, to contemplate “thinking itself,” and to perceive reality in its fullness rather than through an artificially imposed lens. Chestertonian orthodoxy expands one’s mind, offering liberation rather than restriction.

This dual perspective reveals an interesting reversal: Chesterton’s orthodoxy is Orwell’s unorthodoxy. Those who maintain a sincere faith and moral conviction stand as a counterforce against dominant narratives, just as freethinkers threaten the Party’s authority in 1984. This is why Christians have been persecuted in every age, both in open and bloody ways and surely in subtle discriminatory ways, the past two millennia. Christians are a threat to human power structures because they answer to another power, and therefore they cannot be controlled. But if Christians are truly plotters in every age as their persecutors claim, then it can only be said in the sense that Christians have always plotted the healing of the sick, the defense of the poor, the application of true justice as well as mercy and forgiveness, and ultimately the salvation of the world.

On the flipside, Chesterton’s unorthodoxy is Orwell’s orthodoxy in 1984. It is a form of intellectual suicide, the tragic cessation of all thinking. When thinking stops, so does true agency, eroding the essential aspects of our humanity made in God’s image. And without the freedom to think and act independently, what of the human spirit remains?