When G.K. Chesterton celebrated his 100th birthday in 1974, he had been in his grave for nearly forty years. I, too, missed the birthday party, but I was still alive. I was a sophomore in high school, and I was a big fan of C.S. Lewis, something that would lead me to discovering Chesterton a few years later.

But I did have one interaction with GKC at the time of his centennial, even though I did not realize it at the time. I had been given a blank book, and I was busy filling it with my own shallow and juvenile musings, some of which were actually amusing. Dispersed throughout the volume were several significantly less shallow quotations that I had gathered from here and mostly there. One such nugget was from none other than G.K. Chesterton. It was a misquotation, but it was mostly right. I have no idea where I found it and certainly had no idea who he was.

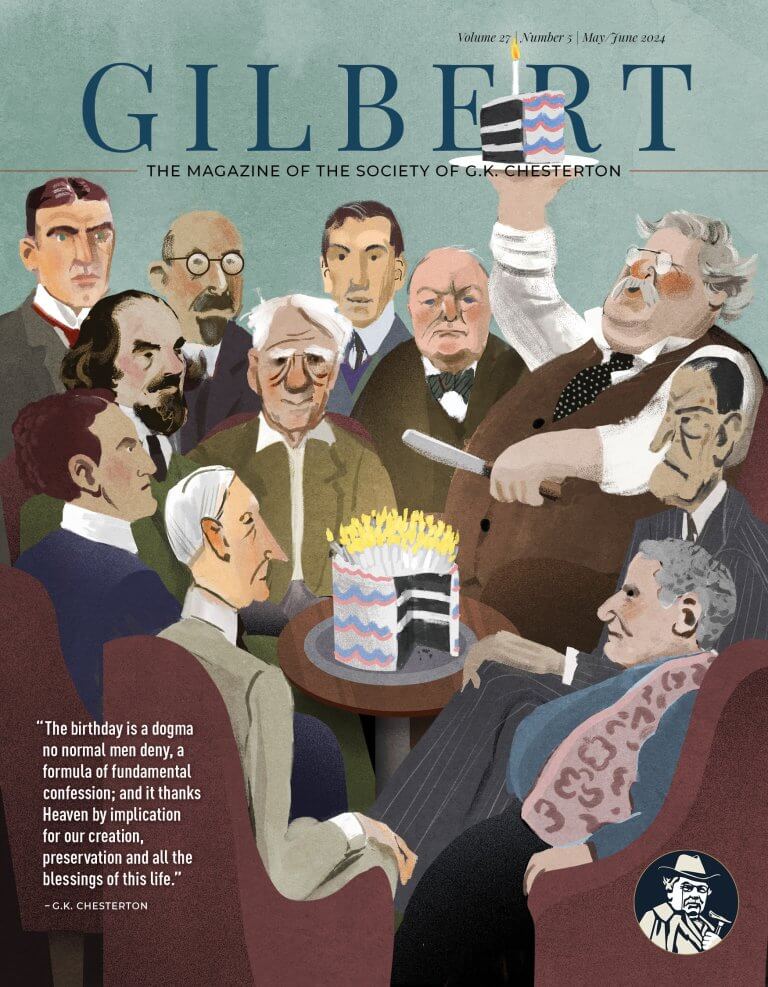

Since that rather unpromising beginning, both GKC and I have aged fifty years. He hasn’t gotten any older, but I have. Not only has he not gotten older, he keeps being new. He is new for everyone who discovers him, and there are more and more such people with every passing year. After I had a proper introduction to him (or not proper, as it were, since he crashed my honeymoon), I went on to enjoy the sublime privilege and thrill to play a role in introducing him to others. Our circle keeps growing.

But why does Chesterton keep being new even to those who have known him for a long time?

I think it might be partly explained in the title I happened to have bestowed on him: the Apostle of Common Sense.

One of the main things that Chesterton says about Charles Dickens, whose work he so greatly appreciates, is that he represents “the conjunction of common sense with uncommon sensibility.”

Now, because of Jane Austen we regard “sense” and “sensibility” as opposites, but Chesterton says they are actually the same. “They both mean receptiveness or approachability by the facts outside us.” Still, there is a “popular distinction between sensibility and sense, particularly in the form called common sense. Common sense is a sensibility duly distributed in all normal directions; sensibility has come to mean a specialized sensibility in one.”

It is quite apparent that Chesterton’s common sense goes in all directions. Whatever subject he takes on, he sheds light on it; he gives us a deeper understanding of almost everything, and makes us suddenly recognize something familiar in what we had considered strange. But he also has that uncommon sensibility that makes us realize what is strange in the familiar things.

Chesterton’s sensibility is uncommon in that it is not specialized. It is not narrow. He has the same interests as the ordinary person, but he feels them more intensely, that is, with a greater sensibility, a deeper awe, a wider wonder. Again, we can say of Chesterton what he says of Dickens, that he “liked quite ordinary things; he merely made an extraordinary fuss about them.”

Thus he makes an extraordinary fuss about, well, Charles Dickens, elevating this popular storyteller to one of England’s literary giants. Thus he gives undue attention to the ordinary detective story and creates a glorious morality play. He prophetically defends the commonest of all things – the family – against a society that separates sex from marriage, husband from wife, mother from child. He praises the ordinary man and the dignity of the laborer against a heartless and thoughtless system that would replace them with machines or turn them into machines. He makes a fuss about bread, the basic product of the land, and wine, the traditional pleasure of the people that puritans and prohibitionists would take away, and shows that God himself makes a similar fuss about these ordinary things by changing them into his body and blood. St. Francis of Assisi goes from being a statue in the garden to reflecting the light of Christ as the moon reflects the sun. St. Thomas Aquinas goes from being a dumb ox to uttering the most profound truths of existence and taking the highest seat among the philosophers. St. Peter goes from being a shuffler, a snob, and a coward to the bravest and most deliberate of men, crucified upside down, where “his humility was rewarded by seeing in death the beautiful vision of … the landscape as it really is: with the stars like flowers, and the clouds like hills, and all men hanging on the mercy of God.”

The Society of Gilbert Keith Chesterton works to keep alive the legacy of this writer, whom we believe to be not only witty and wise, but also holy. And the way we carry on this legacy is by making an extraordinary fuss about ordinary things. A prime example would be starting a school – and then a network of schools. Students are ordinary things, and we make an extraordinary fuss over them. As we should.

Our motive is eloquently summed up in a Chesterton line that he never wrote, but was recorded by his secretary in a thoughtful moment when GKC interrupted himself writing a detective story:

“If seeds in the black earth can turn into such beautiful roses, what might not the heart of man become in its long journey towards the stars?”

ABOUT DALE AHLQUIST

Dale Ahlquist is President of The Society of Gilbert Keith Chesterton, a worldwide lay apostolate dedicated to Catholic education, evangelization, and the social teaching of the church. He leads the Society’s Chesterton Schools Network, which exists to inspire and support the creation of joyfully Catholic, classical, and affordable high schools around the world. Learn More