Joy

Chesterton on Joy

Joy, which was the small publicity of the pagan, is the gigantic secret of the Christian. (“Authority and the Adventurer,” Orthodoxy)

G.K. Chesterton Tweet

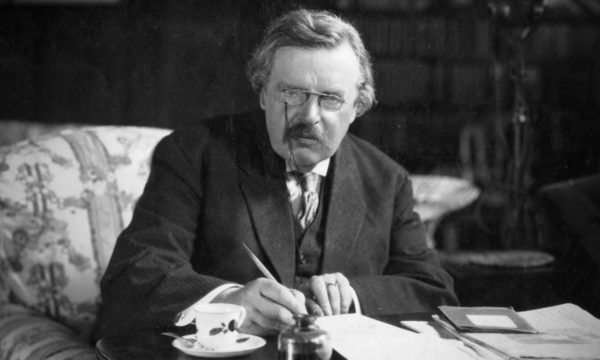

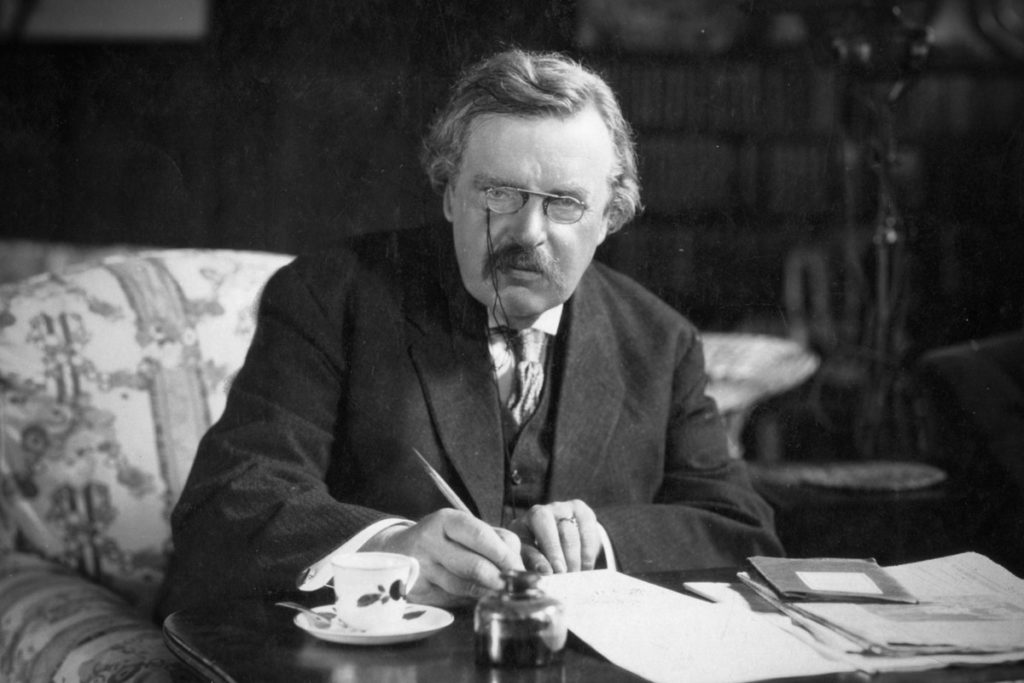

Chesterton says that it is a first principle that men desire happiness. Chesterton’s own joy was one of the most characteristic and attractive things about him. He represented a distinct contrast to the writers and thinkers of his day, who were sour on the world and everything else, even being angry at the God they did not believe in. Chesterton’s joy came first of all from being thankful for everything, starting with the undeserved gift of life, of existence. This is why he said “Thanks are the highest form of thought,” and “Gratitude is happiness doubled by wonder.” He found joy in his faith, and joy in God’s creation, especially the most entertaining element of creation: people. But he understood that most of the world was not joyful, that though men desire happiness they fail spectacularly to achieve it.

“Modern men have utterly lost the joy of life. They have to put up the miserable substitute of the joys of life. And even these they seem less and less able to enjoy.” (“Seven Days Hard,” Broadcast talk, 1934)

He observed that people merely seeking after pleasure have lost the art of enjoyment. He saw that modern poetry and modern literature had not produced any writers who seem to enjoy anything, and we are left with pessimistic poetry “which began at its best by describing pain; and has now descended to describing irritation.” (New York American, Jan. 16, 1932)

Joy is something like common sense. It is normal, it is hard to define exactly. “Normal people enjoy special occasions without knowing why, just as the learned, lofty, cultivated, enlightened people despise them without knowing why.” (Illustrated London News, Jan. 3, 1925)

And we have a duty to spread joy. “Charity is not giving rewards to the deserving, but happiness to the unhappy.” (Illustrated London News, Dec. 8, 1906)

And there is a paradoxical element to joy, that is, it is best when unexpected. “There are some people who would hardly accept any direct happiness, unless you sprang it on them as a surprise.” (The Surprise, Act II,Sc.III)

Man is more himself, man is more manlike, when joy is the fundamental thing in him, and grief the superficial. Melancholy should be an innocent interlude, a tender and fugitive frame of mind; praise should be the permanent pulsation of the soul. Pessimism is at best an emotional half-holiday; joy is the uproarious labour by which all things live. (“Authority and the Adventurer,” Orthodoxy)

G.K. Chesterton Tweet