Hope

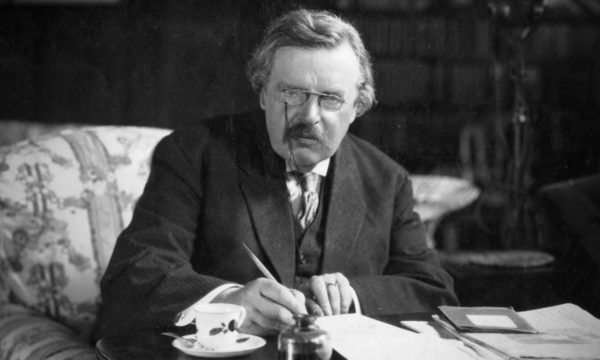

Chesterton on Hope

Hope means hoping when things are hopeless, or it is no virtue at all. (“On Paganism and Mr. Lowes-Dickinson,” Heretics)

G.K. Chesterton Tweet

Hope is a defiant thing. It is only the for the one who can “hang on for ten minutes after all is hopeless, that hope begins to dawn.” (The Speaker, Feb. 2, 1901) Every real hope, says Chesterton, is a forlorn hope. It is “the thing that never deserts men and yet always, with daring diplomacy threatens to desert them.” But the man who has lost hope is truly dead.

Hope is different from optimism. In fact, when Chesterton was about to be received into the Catholic Church and was reading the Penny Catechism, he was struck by teaching that the two sins against hope are presumption and despair. He reflected: “The heresies that have attacked human happiness in my time, have all been variations either of presumption or of despair; which, in the controversies of modern culture, are called optimism and pessimism.” (“The History of a Half-Truth,” Where All Roads Lead) The pessimist is obviously given to despair. But the optimist, with his presumption, has also, in effect lost hope. The point about hope is that it is humble. It does not presume the thing that is hoped for.

Ironically, hope is always associated with youth. But as Chesterton points out, “youth is the period in which a man can be hopeless. The end of every episode is the end of the world. But the power of hoping through everything, the knowledge that the soul survives its adventures, that great inspirations comes to the middle-aged. God has kept that good wine until now. (“The Alleged Optimism of Dickens,” Charles Dickens)

“The heresies that have attacked human happiness in my time, have all been variations either of presumption or of despair; which, in the controversies of modern culture, are called optimism and pessimism.” (“The History of a Half-Truth,” Where All Roads Lead)

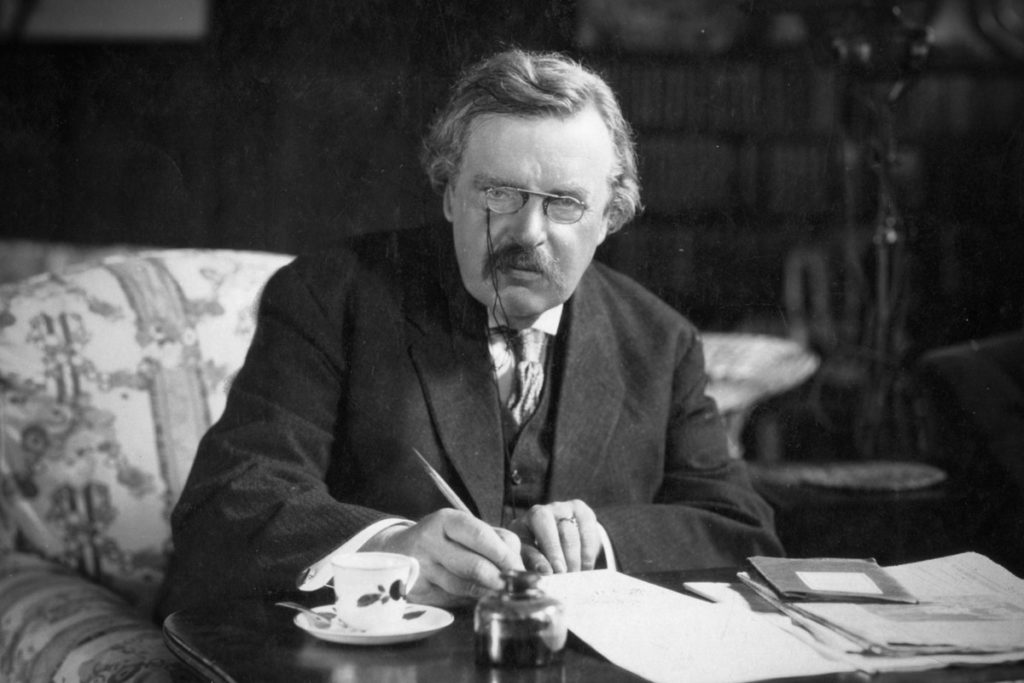

G.K. Chesterton Tweet